Embodied Learning Lexicon: B is for Breath

In a culture that persistently lures towards a distrust of what cannot be seen, our physical reality is becoming increasingly invisible. This text reflects on one of the most basic, yet important, factors of our physicality: breath. I will examine the phenomenological and ecological implications of a culture that too often takes breath for granted, and ask: What can a pandemic which targets the lungs teach about a cultural relationship with grief?

Many people have forgotten how to breathe in a way that fully nurtures the body and enables it to discharge tension. We spend most of our time sitting: in cars or on chairs, making less and less use of the muscles which help sustain the breath.[1] When seated on the computer, arms and shoulders forward, the body is positioned in a way which makes it nearly impossible to breathe deeply.[2] The breath becomes shallow, perhaps the diaphragm contracts, and perhaps the chest muscles become tense.[3]

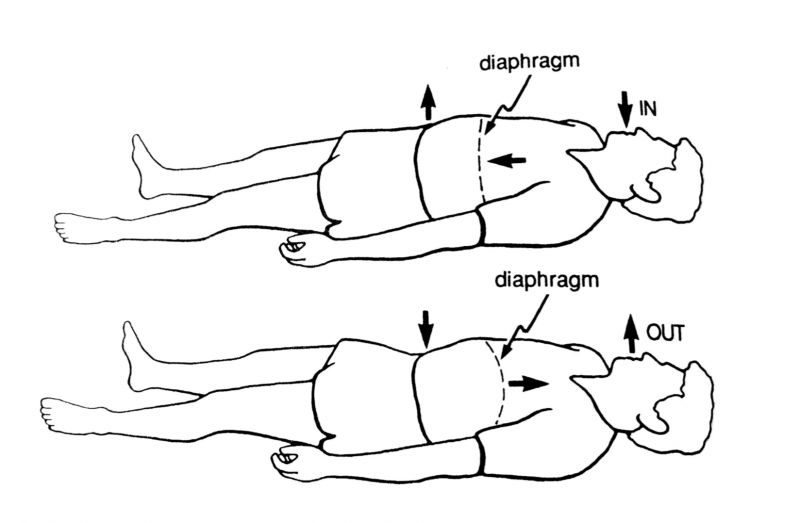

The diaphragm plays an important role in the act of breathing. It is a large, umbrella-shaped sheet of muscle which separates the chest’s contents (heart, lungs, and great blood vessels) from the abdomen’s contents (stomach, liver, intestines, etc.). On the inbreath, it contracts and draws downwards, increasing the volume of the chest cavity where the lungs are located. On the outbreath, it relaxes and returns to its original position, decreasing the volume of the chest cavity.[4] The diaphragm is the space which enables the body’s flux of energy to move upwards from the stomach towards the mouth. If we regard the stomach as a delicate nexus of emotion — the place where desires take root — the diaphragm is crucial to releasing them out into the world, into expression. Unfortunately, many factors of daily life heavily restrict the diaphragm: from prolonged sitting, to tense abdominal muscles caused by stress, to restrictive clothing (basically any pair of pants with a waistline that inhibits the belly from rising and sinking fully with the breath).

Diaphragmatic Breathing, MSBR[5]

The world behind the screen also impacts the breath significantly. Any type of screen addresses only the upper half of the body, reflective of a dualist model of cognition and perception, in which the brain is valued over the experiencing body as the source of intelligence. This forced separation of the head from the rest of the body causes shallow breathing in 80% of people, with the remaining 20% usually being individuals who have learned to become aware of the breath in their practices (i.e. musicians, dancers, and athletes).[6] For many, receiving text messages and emails also evokes shallow breathing, or even breath holding.[7] This is because, from the body’s perspective, anticipation is generally accompanied by an inhale. However, the full exhale rarely follows. From the body’s perspective, this action translates to a state of fight-or-flight in the nervous system.[8] As screen-based technologies exponentially become an extension of lived experience, the experiencing body is sustained within a physical state most closely resemblant of anxious stagnation. At a time when daily experiences drift away from the body, and out into image-infused montages behind the screen, there is also a looming lack of clarity regarding the sovereignty of the embodied self as a tangible stakeholder.[9] As Merleau-Ponty describes, “My body must itself be meshed into the visible world; its power depends precisely on the fact that it has a place from which it sees.”[10] This text argues that the limit as to how far our mental experiences can be divorced from our corporeal ones is nearing, and delineates the dangers of this division on humanity and on what we call “the environment.”

What is breath?

Breath is a movement — an unequivocally visible contraction and relaxation of the muscles.[11] This rhythm and pulsation is intrinsic to all life: from the beating of bacterial cilia to the circadian rhythms of our own body and its biochemistry.[12] Each breath exchanges carbon dioxide molecules from within our bodies for oxygen molecules from the surrounding air.[13] This fluxing movement is crucial in exchanging matter and energy with our surroundings, and exemplifies the continual rhythmic exchange that exists between the body and the planet. One could say that our very ability to breathe, in and out, is what makes us relational beings. Artist and Qi Gong practitioner, Maya Dikstein, points out that the sensitive holes through which we breathe allow us to penetrate and be penetrated by our environment. “Imagine if we would be creatures with no holes, hermetic and confined within our own parameters. How boring! The relational aspect of these holes, where our senses are multiplied, creates a continuity within space.”[14] The walls of our homes may be static, but twenty thousand years ago, humans lived in an environment that breathed. As babies, we are born out of a realm of constant movement and placed onto a bed within hospital walls. This moment, which we have all experienced and accepted, marks a leaving behind of the living world we knew during the first nine months of our lives.[15]

Breath is a “fundamental, rhythmic, flowing life process.” In this life-affirming process, noticing the breath does not infer a need to control it. In fact, trying to control the breath is counterproductive.[16] One becomes aware of the breath not by thinking about it, but by witnessing the sensations associated with it. In mindfulness practices, the focus of breathing usually lies in the belly, far away from the head and the thinking mind.[17] In learning to be aware of the breath, it is firstly important to remember that there is no correct or incorrect way to breathe. In simply observing the breath, one can learn to be flexible in attending to any process that cycles and flows.[18] In this way, breath is also an utmost reminder of the body’s permeability, constantly existing in response and relation to its internal and external environments. While awareness of the breath infers awareness of the vulnerability of being a body in the world, noticing the breath can also help the body feel safe and anchored in presence.

If you would like to practice noticing the breath now, here is a short written exercise. If this does not feel intuitive for you at this moment, you are invited to continue reading.

Begin with an inhalation through the mouth.

With a wide open jaw, pull the air in generously.

Allow the exhalation to exit your body

through a wide open jaw.

Following this open-jawed breath

Just notice the quality that the sensation brings in,

allowing the body to become part of the situation.

If you are reading this, your vision is focused on a point in front of you.

Maybe try playing with the focus,

Passing it to the peripheries of your vision.

Defocusing to the sides

before coming back to the screen.

Let the breath become soft,

as it regulates it back

to whatever your breath wants to be right now.

Perhaps with the inhalation, the chest wants to rise.

Perhaps on the exhale, the tissue around your pelvic floor softens a bit.

Whether these things do or do not happen,

all you are doing is listening, noticing, holding space.

Maybe letting go of anything that does not need to be present with you right now.

You may be happy to know that breath is easily contagious, both on a biological and emotional level. When we breathe slowly and deeply, we are experienced differently than when we breathe quickly and shallowly. This is partially thanks to mirror neurons, which exist in the frontal lobe of the brain. Mirror neurons fire when we either perform a movement, or observe the same movement performed by someone else. Whether we execute a motor action, or simply perceive it in another, the same brain areas are activated in embodied empathy. This action beautifully portrays the means by which the experiencing body is “electric, biological, and cultural,”[19] porous to inputs from its dynamic, living, and breathing environment. Mirror neurons clearly demonstrate how closely cognitive concepts and sensory-motor activity are coupled in the brain,[20] and exemplify why the thinking and experiencing body can not exist in isolation.

How do scratch-proof, super-retina experiences of the world[21] influence one’s sense of interrelationality? What happens to the body left unattended in its chair, as the mind is lured, by means of physio-cultural addiction, into binary and frictionless realms of communication? Is a culture which takes breath for granted one which denies its own permeability?

Contemporary screen-based technologies relate to the eyes as the body’s frame of reference to the world. From the body’s perspective, the more the full scope of embodied experience is limited to one or two senses, the more the body’s sense of focus and space gets lost. This experience easily becomes one of limitation and anxiety, as so much of daily experience is perceived in isolation.[22]

Being a body in the world involves friction that escapes the virtual, reflective of certain perceptions of what technological progress looks like. In his text The Universal Right to Breathe philosopher and political scientist, Achille Mbembe, delineates this deep interweaving of a cultural incapacity to admit being a body in the world, and the means by which this deficit is sharply magnified in realms of technological subjection. “Try as we might to rid ourselves of it, everything brings us back to the body. We tried to graft it onto other media, to turn it into an object body, a machine body, a digital body, an ontophanic body.”[23] Western culture is, afterall, notorious for its unsettling ways of dealing with the immateriality and the discomfort inherent to life.[24] Behind the screens of laptops and smartphones, our ghostly reflections are held captive in boundless non-place, as the body is deemed defunct. When lived existence takes on the form of image, video, and text, the body-mind is left to grapple with the staggering illusion that nothing ever really dies.[25] Death is rather reduced to a monumentalized surface — from a tombstone which grows miraculously from the earth like tulips,[26] to the iPhone — a monolith through which we might try to reach those who are not-quite-there.[27]

In his text, Mbembe depicts the violence of this perceived disconnection from the vulnerability of being a body in the world towards humanity, and all life, as one breathing organism. He suggests that we have never really learned how to die, as bodies do. And as such, have never learned to live with all living species, human or virus. In attempting to escape the pain and grief of embodied reality through the digital, we ultimately presume an indeterminable war on life.[28] In turning to the digital as a refuge from the grief of being a body in the world, life becomes isolated behind screens, between walls, within gated-communities, and sanctified borders. Yet life cannot exist without breath. The powering and cooling of the infrastructures necessary to sustain a world at distance[29] would wreak even greater damage to the lungs and the body of the earth. The realization that breath is therefore far beyond a biological function, but is a constant reminder of the invisible bond we share with all life is perhaps the most vital lesson this pandemic can offer. In the same breath, breath is a universal right, which cannot be quantified and can never be appropriated.[30]

Listen up everyone! We have just been informed

that there’s an unknown virus that’s attacking all clubs

Symptoms have been said to be

Heavy breathing, wild dancing, coughing

So when you hear the sound, who-di-whoo

Run for cover motherfucker!

— Missy Elliot, Pass That Dutch (2003)

To conclude, I would like to briefly return to the notion of the body as a microcosmic map of the environment and the cosmos. What might the body-map reveal about larger and more extensive maps of being in the world? For one, in Chinese medicine the lungs are associated with sadness and grief. It is no secret that we are living in a time of tremendous, if not unprecedented, grief. The sedimentary trauma of generations of institutionalized racism and the dissipation of the planet’s resources weigh heavy on the lungs. From the body’s perspective, grief and sadness often translate as physical pain. In western culture we are generally taught to deflect pain, as it is often confused with suffering. From the body’s perspective, however, pain is actually clear and life-affirming information. Pain which remains stagnant within the body over time can evolve into suffering.

When one accepts that the body shapes how we think and act in the world, one quickly realizes the means by which the body is an archive. Activating this archive can begin with simply attending to the breath and noticing its healing qualities. Addressing any grief within the body can also grant one tremendous freedom to perceive the pleasure of aliveness, and the body as the very frame of that aliveness.[31] Even simply noticing the breath can therefore become fertile ground to fathom the imprints of life on the permeable, sensing bodies we share.

The Embodied Learning Lexicon was developed for the Embodied Knowledge Bureau, an interdisciplinary platform proposed by Micaela Terk (Sandberg Instituut, Design Department), Sheona Turnbull (Sandberg Instituut, Design Department) and Yotam Shibolet (PhD Researcher & Lecturer at Utrecht University, Department of Media and Culture). This platform aims to reconceptualize creative practices from an embodied and enactive approach. By delineating how the body plays an inseparable role in our perception of the world, we hope to speculate on how the systems we live in may be approached through a more deeply embodied lense.

This publication is commissioned by the Editorial Board as part of the series 'Future Practices'

'Future Practices' is the framework for a series of publications on current topics that stimulate or question intercurricular education at the Gerrit Rietveld Academie. Various interdepartmental or interdisciplinary duos and teams have been asked to create a contribution in a format of their choice, such as a podcast, a text or an audiopiece. These collaborations originate in the first Open Call for Intercurricular Programmes in November 2020. Because of the many promising proposals, the editorial board decided to select 6 collaborations and asked these to publish their research via extraintra.nl in 2021.

Avi Grinberg, “Humans as a Body,” in Fear, Pain, and Other Friends (The Grinberg Method Holland B.V., 2016), p. 113.

Linda Stone, “The Connected Life: From Email Apnea To Conscious Computing,” HuffPost, July 5, 2012, https://www.huffpost.com/.

Avi Grinberg, “Humans as a Body,” in Fear, Pain, and Other Friends (The Grinberg Method Holland B.V., 2016), p. 113.

Jon Kabat-Zinn, “The Power of Breathing: Your Unsuspected Ally in the Healing Process,” in Full Catastrophe Living: Using the Wisdom of Your Body and Mind to Face Stress, Pain, and Illness (New York, NY: Bantam Books, 2013).

Jon Kabat-Zinn, “The Power of Breathing: Your Unsuspected Ally in the Healing Process,” in Full Catastrophe Living: Using the Wisdom of Your Body and Mind to Face Stress, Pain, and Illness (New York, NY: Bantam Books, 2013).

Brian Robinson, “Is Your Computer Screen Stealing Your Breath?,” Forbes, November 14, 2020, https://www.forbes.com/.

Eric W. Nolan, “Preliminary Study of the Psychophysiological Effects of Texting,” PsyPost, May 5, 2010, https://www.psypost.org/.

Linda Stone, “The Connected Life: From Email Apnea To Conscious Computing,” HuffPost, July 5, 2012, https://www.huffpost.com/.

Micaela Terk, “Techniques of Invisibility,” in Techniques of Invisibility (Berlin: Goodbye Books, 2018), p. 13.

Maurice Merleau-Ponty, “The Philosopher and His Shadow” Signs. (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1964), 166.

Micaela Terk, Barbara Droubay, and Yaara Neiger, “A Body of Experience,” in Techniques of Invisibility (Berlin: Goodbye Books, 2018), p. 90.

Jon Kabat-Zinn, “The Power of Breathing: Your Unsuspected Ally in the Healing Process,” in Full Catastrophe Living: Using the Wisdom of Your Body and Mind to Face Stress, Pain, and Illness (New York, NY: Bantam Books, 2013).

Ibid.

Maya Dikstein, “Ping Pong Talk, ‘32,’” Vimeo (Vimeo, May 29, 2020), https://vimeo.com/424068979.

Micaela Terk, Barbara Droubay, and Yaara Neiger, “A Body of Experience,” in Techniques of Invisibility (Berlin: Goodbye Books, 2018), p. 90.

Jon Kabat-Zinn, “The Power of Breathing: Your Unsuspected Ally in the Healing Process,” in Full Catastrophe Living: Using the Wisdom of Your Body and Mind to Face Stress, Pain, and Illness (New York, NY: Bantam Books, 2013).

Ibid.

Ibid.

Rolf Pfeifer and Josh Bongard, “Development: From Locomotion to Cognition,” in How the Body Shapes the Way We Think: A New View of Intelligence (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2007), p. 171.

Micaela Terk, “Envisioning Invisibility,” in Techniques of Invisibility (Berlin: Goodbye Books, 2018), p. 9.

Suzan Kozel, Closer: Performance, Technologies, Phenomenology. (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2007), 33.

Micaela Terk, Barbara Droubay, and Yaara Neiger, “A Body of Experience,” in Techniques of Invisibility (Berlin: Goodbye Books, 2018), p. 85.

Achille Mbembe, “The Universal Right to Breathe,” trans. Carolyn Shread, University of Chicago Press Journals, April 13, 2020, https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/.

Micaela Terk, “Hauntology of the Cloud: on Memory and the Ghostliness of Virtual Space,” Medium (Medium, January 10, 2020), www.medium.com/@terkmicaela/hauntology-of-the-cloud-on-memory-and-the-ghostliness-of-virtual-spac e-53e6225a0335.

Micaela Terk, “Envisioning Invisibility,” in Techniques of Invisibility (Berlin: Goodbye Books, 2018), p. 13.

Fisher, Mark. “Is It Still Possible to Forget?” Spike Art Magazine 42 (2014). https://www.spikeartmagazine.com/en/articles/qa-mark-fisher.

Micaela Terk, “A Futurist Eulogy,” Medium (Medium, June 12, 2020), www.medium.com/@terkmicaela/eulogy-to-a-future-body-91239b545901.

28 Micaela Terk, “Hauntology of the Cloud: on Memory and the Ghostliness of Virtual Space,” Medium (Medium, January 10, 2020), www.medium.com/@terkmicaela/hauntology-of-the-cloud-on-memory-and-the-ghostliness-of-virtual-spac e-53e6225a0335.

Achille Mbembe, “The Universal Right to Breathe,” trans. Carolyn Shread, University of Chicago Press Journals, April 13, 2020, https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/.

Ibid.

Micaela Terk, “Envisioning Invisibility,” in Techniques of Invisibility (Berlin: Goodbye Books, 2018), p. 13.