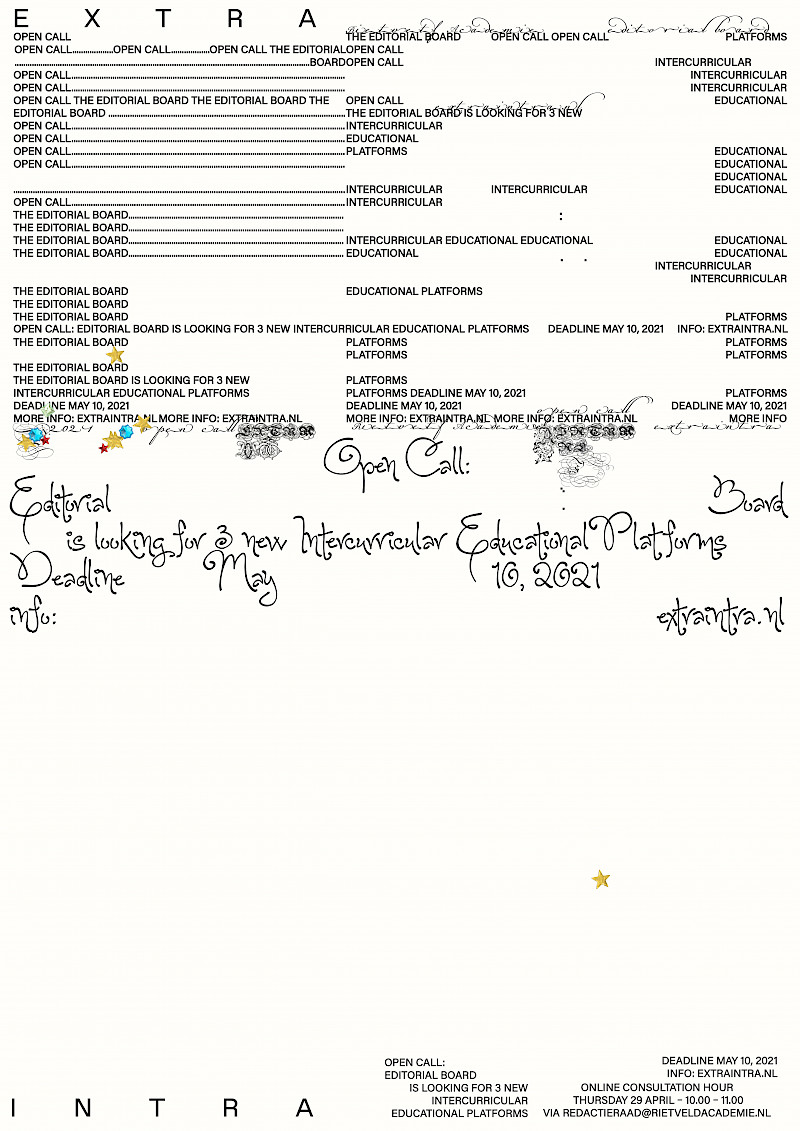

(closed) Open Call: Intercurricular Educational Platforms - round 2

The editorial board invites students, teachers and workshop specialists from the Gerrit Rietveld Academie to team up for two semesters and create an intercurricular educational platform. The Quality Agreements 2019-2024 budget offers the possibility to support new educational platforms in the upcoming years. Three new platforms will start in September 2021, focusing on one of the following topics: ecology, future commons, embodiment, relationality, the future of materialisation, future pedagogy, future art and design economies, technology, future philosophy, future feminisms or future politics.

What?

An intercurricular platform offers additional, small-scale and intensive education related to current topics and innovative issues, open to students from all departments of the BA and MA programs. A platform is a way to bring students, teachers and workshop specialists together around a topical question that will form the driving motivation for their knowledge production. The platform functions as a sort of research group. The research, knowledge and experiences that are generated by the platform will be shared with the wider community at the academy. All platforms define their own working method. The platforms - currently Writing Classes, Recipes for a Technological Undoing and the Garden Department - add an enriching layer of content, without displacing regular education. The platforms thus position themselves in the space between, outside and next to the educational departments, or even outside the academy.

The editorial board is looking for proposals for new platforms that:

- are initiated by a core group of 3 people, who can be students, teachers or workshop specialists. Each core group should include at least one student.

The teacher or workshop specialist preferably already has a position in the academy. - stimulate interdisciplinary and trans-departmental collaborations and/ or establish connections with actors outside the academy, through projects in which cooperation, self-organization, research and new ways of working are central.

- focus on a specific topic within the list of themes selected by the editorial board (see below) that are currently not addressed within the existing educational departments, but do arise from the needs of students and teachers and from the educational issues that play a role there.

- claim experimental forms of education, thinking and making, and arise from urgent questions in art and design and society at large.

Other requirements:

- The core group is responsible for initiating the platform, organising the activities of the platform, communicating reports and events, updating the editorial board, managing the budget, publishing updates on the website, and sharing the outcomes with the rest of the academy and s/he / they will be responsible for delivering the educational end results of the platform. They will be supported in these tasks by the coordinator of the platforms who will assist with the budget, communication and planning.

- Members of the core group will support each other with practical matters including initiating the platform, organising meetings and setting up public programs. They will be compensated for their efforts for these practical matters only. NB students do not receive compensation for the time spent on their education.

- A platform should be open to students from both the Rietveld and Sandberg.

- A platform should have (a minimum of) 10 participants (who are currently involved in education at the Rietveld or Sandberg), alongside the core organisational group.

- A platform will exist for at least two semesters (budget mentioned above is for 2 semesters).

What do we offer?

- a budget of € 13.500 for each platform, which will last two semesters.

- an online platform for the publication of the progress and results of the intercurricular platforms

- a coordinator that facilitates and coaches (0,1 FTE per platform). The coordinator facilitates and coaches the platform with managing the budget and delivering a financial report, guarding the quality, substance and schedule of the platform, publishing updates on the website, updating the editorial board and sharing the outcome and end result with the rest of the academy.

- 2 meetings with the editorial board

How to apply?

All students, teachers and workshop specialists at the academy are invited to respond as a small core group to initiate a platform around one of the topics below. You can respond to this Open Call with a project plan and a budget. These should be submitted together in no more than three A4s. Please include:

- Names of all initiators and a description of their previous and current positions in the school

- In case your platform already exists: please be clear about previous and current activities, previous and current funding, and clarify how your new proposal relates to this

- Description of prospected participants

- How your proposal connects to one of the topics selected by the editorial board

- Your specific approach to one of the topics mentioned above, and how your approach matters to the academy

- A description of your activities and a plan for the 2 semesters your platform would run for in relation to the budget

- A budget

- Description of your final presentation (e.g. exhibition, publication, lecture etc)

- Insight into your educational goals and results

Send your project plan and budget to redactieraad@rietveldacademie.nl before May 10, 2021. The editorial board will select the 3 proposals in May and June 2021, and will take into account (amongst others): Urgency of proposal, feasibility, originality in either (new) educational model or approach, or topic.

The selected groups will be informed in late June 2021 and will initiate their platform starting September 2021.

Questions?

The editorial board will host a digital walk-in consultation hour on Thursday 29th April 10.00 – 11.00. Please send an email to Tessa Verheul and Joram Kraaijeveld for additional information.

List of topics

Embodiment

Does your body equal your person? When does your body become a symbol for something else? How can you be the embodiment of a notion such as hope? How many bodies are needed to form a social body of resistance? Ideas and theories about individual bodies, social bodies and digital bodies have recently been rebutted and reworked in such a way that the body seems to be lost, while simultaneously present to demonstrate against its loss. Perhaps the digital world is not entirely virtual after all, but rather a concrete and biopolitical infrastructure? Perhaps the notion of identity is not, in fact, cosmopolitan, but rather the consideration of the fleshiest of flesh? When taking into account gender, race or sexual preferences the body is back from never having gone at all. Still, your body seems to be so much more than a body. What could these new understandings mean for the practice of art and design?

Relationality

For decades artists have taken the intersubjective as a formative principle for their artistic practice. Many social events have been organized including sit-ins, tea ceremonies and other kinds of social meetings. These have been exhibited as artistic practices in and outside of museums. As these practices have been collected and canonized the question of whether they are art or not seems to be decided upon. What remains relevant is the question: how do we relate to one another? Are intersubjective relations necessary for an individual subject to identify oneself or simply to live? What kind of human relations and what kind of social contexts would we like to develop? There seems to be a shift from the artist as the instructor or director of situations to more collaborative and non-hierarchical encounter-based models.

Future Pedagogy

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic it was clear that we were facing a new reality. In 2020 the shift to online education at the Gerrit Rietveld Academie meant it was urgent to rethink models of critical pedagogy in light of the current situation. The academy is an environment for learning how to shape a practice and life as an artist or designer. Critical pedagogy’s vision of education is that it is not an environment for opportunistic or purely private matters but a collective space for learning to develop personal ideas in relation to others. Can critical pedagogy help us to refocus the important practice of learning so that we can find ways to relate to the new reality we find ourselves in? What might a socially just pedagogical approach look like, particularly when working with people from around the world within an Amsterdam-based Dutch institution for art and design?

Future Commons

The commons, as a way to manage renewable natural resources in a communal ways rather than in public or private ownership, has been an inspiration for many artist and designers over the last decade. To what extent can this notion be extended to art and design education? Which forms of art can become a commons, and how? In which ways can we cultivate and sustain the commons through art practice? Which forms or art are co-managed by self-organizing communities where maintenance, care, sharing, cooperation, ecology and diversity are important? Can we create a commons of education, and what would be the characteristics of the educational tools that belong to our community?

The Future of Materialisation

The workshops provide a space in the academy for experimentation where students can learn technical and material skills and develop their personal style, interests or materials. All of the existing available techniques and materials are being questioned and challenged by designers and artists, in part due to developments in industry, technology, economy and artificial intelligence. The ecological crisis is creating an awareness of how each material is a choice. In considering the origins, uses and the subsequent consequences of particular materials we challenge our relationship to materiality and pose new questions around the education of future designers and artists. How can workshops relate to these issues? The declining number of public workshops and downsized studio spaces make it hard for artists and designers to play and experiment freely, let alone learn new techniques after graduation. How can students put their experimental visionary projects to use in a way that is worth pursuing for manufactures, and thereby have an effect on industries? How can students be prepared to operate in a world of design where they are dependent on industrial processes? Do workshops have the responsibility to keep discovering new materials? And if so, should they function as experimental laboratories?

Future Art and Design Economies

When considering the future of our societies and economies it may be interesting to think about how they are entwined with the role of art and design, and its place within them. Art may be regarded by the majority as either an individual signature work that enters the art market as a commodity, or as a public form supported by funding bodies (or a combination of the two). However, art is also seen as an autonomous vehicle for social, political and innovative ideas, allowing us to tell untold stories or offer critical perspectives as if it doesn’t partake in the economy. Although design might be regarded as the invention and creation of objects that can be put to use and offer all sorts of solutions for people and markets, or as a critical practice to improve our societies, it is primarily still considered a product within an economy of supply and demand. What kind of economies can artists and designers create in the future where both roles might lead the way as a vehicle for social, political and innovative change instead of a venture for economic returns? What position can artists and designers claim in a future economy? What kind of roles does this give the artist or designer within society?

Ecology

Artists and designers are critically addressing and creatively negotiating environmental concerns on a local, regional, and global level. These concerns include climate change and global warming, and relate to factors such as habitat destruction, drought, species extinction, and environmental degradation. These emerging environmental arts make use of interdisciplinary research tools and draw on visual culture, art history, political ecology and economics, Indigenous cosmopolitics and climate justice activism. Considering these environmental concerns, what kind of art and design practices are needed in Amsterdam in the 21st century? Do students and designers need to begin by addressing the ‘afterlife’ of every product and start designing a circular economy? If this were possible, what would such an art world look like?

Technology

Technology has never been more incorporated into or fused with our lives than it is at the present moment. How are artists and designers responding to the new conditions technology offers with apps or new digital research methods as well as the practices of data mining, mass surveillance and algorithms? How does the mass ‘creativity’ invited by social media and consequent personal branding redefine our ideas of being an artist or designer? How can artists and designers respond to the apparently abstract but intrusive processes of machine learning and Artificial Intelligence? What if artists and designers have been cyborgs or co-bots all along? How can creative coding give us the tools to reclaim digital and physical spaces?

Future Philosophy

What sort of thinking is needed to understand the art and design practices of today and tomorrow? Which languages, traditions and vernaculars have become obsolete and what needs to be invented to develop a thinking of, a feeling on, a being with, a speculation about, a fabulation of art and design? In the last decade it has become clear that there is a collective desire for change. Modern and post-modern traditions of thinking—which one could call the discipline of philosophy—are no longer satisfactory in explaining the present conditions of our worlds or their artistic and cultural practices. Although the narrative of metamodernism has tried to go beyond the ‘end of history’, the historical periods of modernism and post-modernism, with all their different strands and schools and periodization of thought, have been heavily criticized as too Western, too white, too male, too institutional, too elitist, too inaccessible, and perhaps even too philosophical.

Future Politics

A common way to relate art to politics is by assuming that art and design is political when it represents or works with political issues. For example, when a project concerns public housing or social justice. In this understanding art is political when it gives a voice to those who cannot be heard or when it makes something visible that is either elsewhere or invisible. Over the past few years, a focus on the labour conditions within the cultural sector has offered a new perspective on the politics of art. One of many forms of exploitation in the field of the arts is within the cosmopolitan biennales that exist on the back of the unpaid labour of interns and sponsorship from large corporations. Alongside the politics of representation and the politics of labour, various art projects have generated a ‘politics of politics’ by working with democratic structures, human rights and the rule of law. Many of these projects have offered ways to reimagine the political and have had an influence on decision-making processes that improve, invent or redefine democratic politics. What role can art have in politics in the future? Can art strengthen democratic societies with projects that rehearse or propose democratic procedures? Does art need to do this for its own survival?

Future Feminism(s)

Feminism consists of many intertwining and diverging movements that have previously given us reproductive rights, childcare, bodily autonomy, new property laws and much more— all of which many of us may now take for granted. Like a barnacle on the surface of biopolitics, feminist movements have ultimately concerned themselves with power: who governs, who is governed, who creates, who goes down in history and who gets written out of it. Contemporary feminist practices take many forms and draw attention to the gendered body and its place in digital culture, make space for voices that have been systematically overlooked and work to deconstruct and reshape the misogynist narratives that have structured our society, finding alternatives along the way. How can artists and designers continue to further these goals whilst considering how the structures of the art world and art education are complicit in maintaining inequality? In the wake of sexual harassment and abuse scandals across the world one thing is clear: inequality continues to be rife and the intersections of race, class, gender, disability and sexuality are key to current conversations. What models, collaborations and methodologies can feminist practice offer us in terms of solidarity, political change and imagining alternative futures? What role can artists and designers play in shaping these future feminisms?