TO NOSE. FROM NOSE.

Dear Olya,

I’m writing you a letter from my nose, in the sense that I depart and arrive from the nose and to the nose as I nose. My point is that I have traveled far, but I know that the place of my face that is the “I” where my story unfolds and folds in a void of not-knowing is a song of home-coming too as the paradox of leaving and the impossibility to leave within the breathing time walking upon the soils of the earth bordered by law and tongues drawn and woven into streams of images and semantics. We have known each other for a few months now and one of the things that connect us is the impossibility of speech and the perpetual trying, trying, and trying.

“Let’s write a letter!”

You respond: “first-nose narrator!”

I respond: “nose poetics!”

This leaves us with a first-nose narrator as a coming together of the fragments of how the nose is written, drawn, and inscribed into the social fabric through the effect that it performs upon us, with us and independently of us. Social fabrics are sometimes drawn to search for meanings that collapse into pure abstraction. I think that is why you expressed that you’re worried that the nose gets lost in all of this, or rather that we get lost in everything that surrounds the nose.

In the geographies of our face, the nose is the highest point, as you mention. You see it in the landscapes. Once you start looking, they are like mountains, hills or the towering buildings of cities and towns that serve the purpose of navigation—architecture that sings of the desires of being found. I like this thought. Where people usually see dicks, you see noses. Towering structures are not necessary dicks…indeed. There is a big difference between them, no? Dicks usually find you, and you spend so many of your formative years just escaping them, while the thing with the nose is that despite the stable presence of being here and everywhere it easily gets lost. The thing with searching is that you search in multiple ways because, as it goes for nearly everything, it gets lost in an intersection of losing. One can lose and find in a paranoid way as much as through a longing for reparation, which is a building process tied to an intimate practice of imagination and personal fictions.

Paranoia incriminates the nose through its desire for clarity and law preservation. I’m thinking of the scientific racism within the heritage of Lombroso’s work The Criminal Man (1870). It revolves around the atavistic form—a set of physical characteristics as a ground for criminal behavior that, according to this theory, is tied to the supposed genetic failure of an individual who would therefore be at a less developed stage of evolution, and therefore incapable of joining ‘civilized’ society. The criminal nose is, for instance, a hawk-like nose. The word ‘atavistic’ derives from the Latin ‘atavus’, meaning ancestor. And even though The Criminal Man has been lying in the not-science-anymore-ghost-from-the-past drawer of history, it haunts contemporary technologies of recognition. How many people have been falsely accused of a crime that they didn’t commit, or denied access at a border? The nose is argued to be good biometric material, as it is the part of the face that isn’t so easily distorted by emotion. The camera captures. But what if sensory technologies begin to act as a nose, by suddenly staging meetings between one nose with another nose? What if a technology acquires the ability to smell the chemical composition of breath coming from the very inside of a body, as a fingerprint in the air? Would it be able to sense the presence of someone in the same way as we recognise the people who we love by smell only? As you see, I’ve got a great amount of my own paranoia to deal with. There are specific ways that finding someone by their nose isn't separate from the exercise of violence.

I’m writing this while understanding that it can never act as an argument against trying to find the nose because as I mentioned before, there is a multiplicity of ways to be lost and found. And I still have a lot to say, but that’s for another letter.

With love,

Nastija

-

Dear Nastija,

We spoke of face recognition and it seems unfair that although the technology relies on noses, human beings do not. I could hardly describe someone’s nose unless it is utterly irregular. The nose can enter history only through its flaws, not for its virtues. Memorable noses would shape the weirdest of collections in the eternal history museum of the human body. By severing a nose from the face we create a surrealistic object, sitting on a red, lip-shaped sofa. Such a cliché. Shall we, instead, leave the nose with its face? See it as a continuation, or rather the end of, a face, the highest point of it, when a person is lying on her back, gazing at clouds floating above. I do not agree that noses are emotionless. Imagine how their tips move rhythmically when we read, how they get red when we are drunk or cold, how they wrinkle when we hate someone, how they go up when we raise our head, half-dreaming in a library. The omnipresent emotionality of eyes, hands, and lips has now ousted the noses, now at the very periphery of tools for expressing human emotions. Unfair again. I clearly see the dramatic potential in every nose, a story untold, a book unwritten. You know who does speak of noses? Only people who have not come to terms with their noses! This is my observation. I am one of them, obviously. Otherwise, I would not be writing this letter. The exercise of focusing on your nose (or rather breath) is actually a part of many meditation techniques. I propose a nose meditation, a nose narration, and maybe even a nose landscape painting.

My first nose narration is a multi-layered drama, where the Nose speaks of her coming of age and self-hate, of being different, of growing more and smelling all sorts of troubles but also foreign seas and forests, of looking at itself in the mirror

and trying to recognise in herself those who were there before her. The identity crisis of this Nose is the crisis of familial belonging. The Nose that doesn’t know her history but just wonders why she is so long, so big, so irregular? People complement her uniqueness and one-of-a-kind-ness. But it only makes her more lonely. Quite a grim story, I must say.

In the attempt to understand and embrace the irregularity (or maybe, on the contrary, commonality) of your Nose lies the desire of belonging and knowing where you are from. Nose is a family history reified, like the whole of the human body. But too many songs were sung for the eyes, the hands, the hair. I would like to sing of the noses for a change. As we depart from our homelands, we are severed from our family histories. They gradually become atavistic, our ‘atavus’ (Latin. ancestors) become ‘atavus’, right? And for some of us there was never even a moment where we were united, in touch with these histories. With the passage of time those histories become cloudy, foggy and boil down to simplistic formulas, fables and anecdotes that we automatically reproduce when being asked about our homes and families. In the absence of material evidences our body serves as the only evidence of our familial belonging. It is the centuries of history cast in the shape of the body we live in. And as we are lost in the fog of memories or unknowing, we seek the landmarks, to lay our path. Let the nose be this landmark. The tallest and the most memorable. What does it tell us about the family and the home? My Jewish nose tells the story of displacement, communism and scientific atheism. I want to let it speak and tell the story. And as the story will be told the landscape around it will shape and reveal itself—the swamps for the family members who we never knew, the mountain ridges for the controversies that divided the family, the estuaries of rivers, for the memories that are crystal clear and vibrant. Let the body become the tool for mapping out the geography of our familial memories. And we will start by drawing a small mountain.

This is your Nose.

-

Dear Olya,

I wanted to send you my response Monday but it’s Wednesday now. I’m a bit late. I’ve been stuck with writing. I guess I was tired. I lose my letter writing to small acts of procrastination as a weird mold for pouring my language into.

It doesn’t ask for coherence, words just arrive. Procrastination is the work that is not work, and it’s a way of processing guilt while feeling guilty about it. This morning I was thinking about the knots of the wood of the floor of this room where I’m currently staying in Amsterdam.

The thickness of the rings is defined by the amount of the rain that has been soaking the soil of the tree, which then archives the liquid within its own body. Memories of all the leaking builds this body up. And I,

I’m still ashamed for no particular reason,

shame doesn’t ask for reason,

and my shame

she got no name.

For a while I have been a body bending

and salty skin

I come from homes that have a television in every single room apart from the bathrooms, but I’ve been in bathrooms that have radios. My revenge has always been to forget their language, and by accident I forgot my own tongue too, which got me stuck in a loop of translation as language never truly leaves the body.

Jesse Darling writes in a letter to the translator[1] “As you and I both know, there is no such thing as translation; a text must be rebuilt from the ground up. What I said, or meant to say, eroded by your own will and words. This is how it must and ought to be. In between there is something unspeakable, or unspoken.”

I sometimes want to build myself up too.

If with a photographic representation. I too agree that the nose is not emotionless. I understand it as, twhen thinking in the algorithmic reading of images, the nose is the part of our face that is least distorted by emotion. Emotions disorient the readability of the face, and somehow the nose does not transform enough in that movement to disappear if captured by a camera for the purpose of identification. I tried to find that article again, but I couldn’t.Maybe it is not even true, and maybe it doesn’t matter if it is when trying to think along with these ideas.

I think it’s weird that face recognition is called that because it has very little to do with recognition and everything to do with identification. Recognition is something different.it doesn’t tie your face to your name, or noses to governments, but requires our faces to be entirely distorted by emotion to be recognised by the ones who we love, because we recognize each other through a process built on emotional relationships. Somehow it also makes me think about how we understand and recognise the smells of people who we are deeply attached to. Our bodies are archives of water leaking all kinds of liquids—emotion, sweat and tears.

If singing with the nose would the nose be weeping? It is quite left out indeed, when thinking about lyrical dedications to our various body parts. When songs are sung about crying, there is never a choir of the noses, even though it is as liquid as the eyes in its sonic sensations, of the breathing rhythm and in holding back of its running.

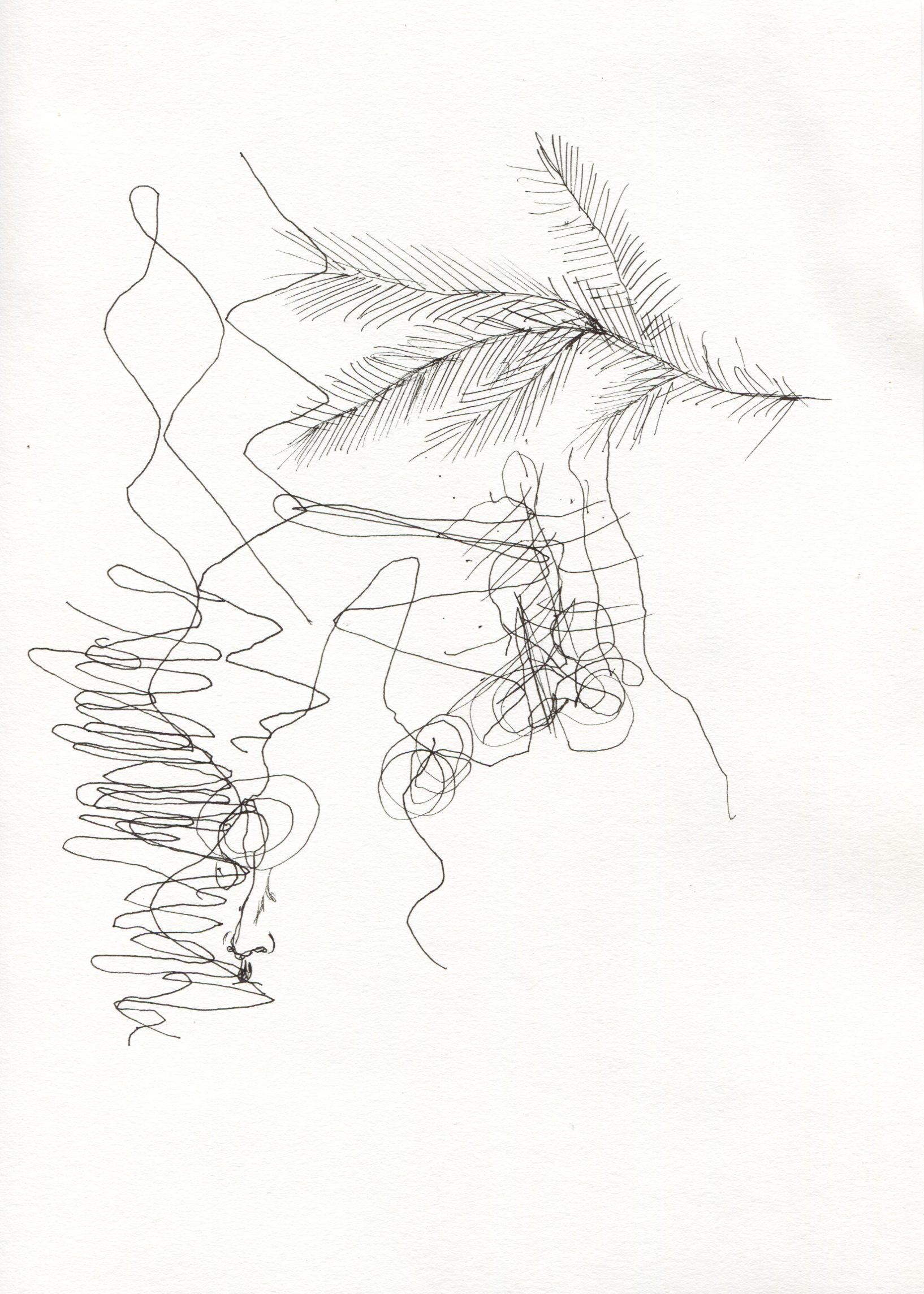

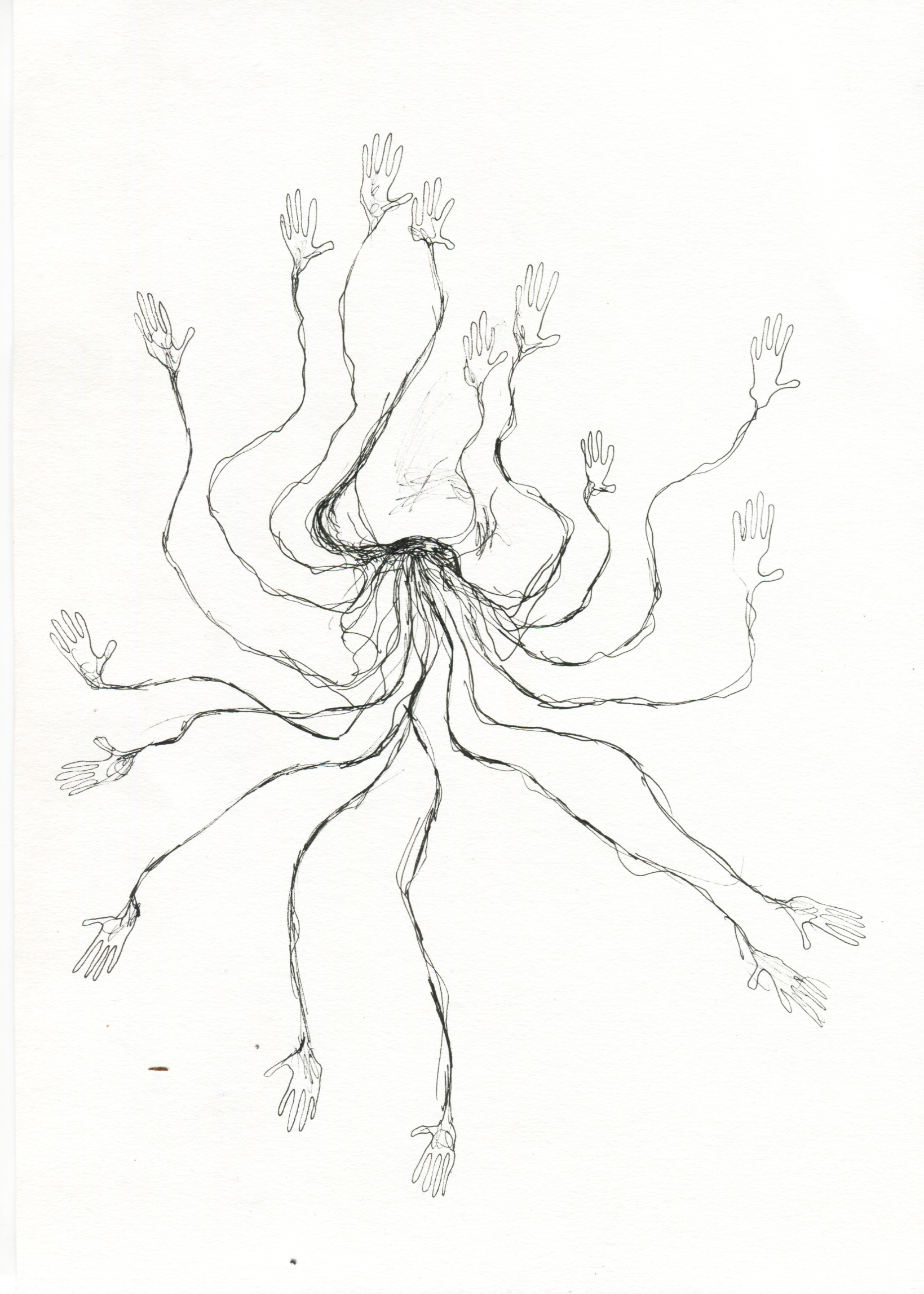

I like the idea of a nose meditation, a nose narration and maybe even a nose landscape painting. I would like to write part of this letter as a drawing, which could also be a form of nose meditation. But before I think about the steps, I must mention that I’m intrigued by the question of irregularity even though I don’t understand what an irregular nose is. We have talked about this before; we share some likenesses in our family histories, especially when it comes to forgetting. When you write “In the absence of material evidence our body serves as the only evidence of our familial belonging. It is the centuries of history cast in the shape of the body we live in,” suggesting the nose to be the landmark for navigation of our personal foggy landscapes of belonging. I can only read this landmark if it’s fictional. You see, my nose lost and reinvented its name in the returning from the camps where my family served ten years as a punishment for coming from the ‘wrong’ country. In many ways, I see myself as a fictional character and I cannot be truly honest with you if I don't lie a little bit. I will meditate, lie, and draw you a self-portrait. I will be recording my steps and invite you to follow me, please send a drawing back.

1) Find a comfortable spot where you feel most at home within the space where you currently find yourself.

2) Close your eyes. Breathe through your nose. Try to follow the rhythm of the breath by transcribing it on a piece of paper. Set a timer for five minutes.

3) Open your eyes and take a moment to have a look at the transcript. Find the place within the writing of the breath that you’re intuitively most drawn to. Hold your pen on that spot.

4) Close your eyes for five minutes again. Take a finger of the hand that is not writing and place it on the spot where you feel that your nose begins. Follow the shape of your nose with your hand while your writing hand transcribes the movement. If your nose begins from multiple places repeat the movement as many times as you need.

5) Open your eyes. Pick a spot on the transcript of your nose and draw it as you imagine it. Do it as fast as possible without thinking too much.

6) Draw the first smell you associate with a homeland.

I have added my portrait on the next page.

As I mentioned yesterday in a voice note, Katya would like to join our letter correspondence. I’m very much looking forward to that, and of course to receiving your next letter.

With Love,

Nastija

-

28-11-2022

Olya replies with a drawing:

-

Dear Nastija (and, I guess, Dear Katya and everyone else who participates in this correspondence from now on),

I appreciate how your drawing exercise pinned down this very poetic and sometimes abstract conversation to the materiality of our own noses and attempts of depicting them. The depiction of the noses, as we discussed previously, seems to be one of the most problematic parts of the nose discourse. I remember when I was a kid I would always start drawing the face from its contours or from the eyes, never from the nose! And it seems interesting that iconography of noses in children’s drawings are often reduced to a nose depicted as a simple line or two dots. The characters given the prominent noses are usually the magicians, villains or Santa Clauses. The rest are endowed with the most generic nose sample, at least that was my drawing philosophy.

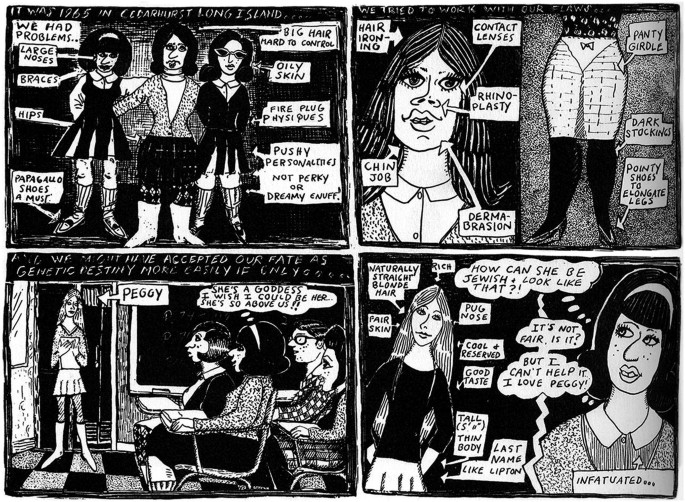

I’ve been reading this book on American Jewish female comic artists and, well, of course they had to come to terms with how to portray themselves, and their noses in particular. They had to commit to ‘finding’ themselves, to affirming their presences, by drawing themselves and their worlds both in the present and over time. I find this idea to be important—as we draw ourselves, we learn how to define ourselves and map out our identity. We affirm our presence by showing that this is me, this is the way I see myself. Nose Job, the comic book by the Jewish American Aline Kominsky Crumb, narrates her experience of watching all of her female peers showing up at high school with “new noses.” Despite pressure from family and friends, ‘The Bunch’ refuses this rite of passage and finds herself, years later, boasting, “So I managed to make it thru high school with my nose!!” The Bunch’s reluctance to conform within her actively assimilating Jewish community paradoxically sets her apart; she becomes an outsider because of her refusal to erase the bodily traces of that identity.[2]

And as formulating your identity, as well as your Jewishness, is a process that continues throughout life, then learning how to see/describe/depict your body must be one of the tools for navigating this journey of self discovery. The book I read continues: “Friedman calls a ‘new geographics,’ one that ‘figures identity as a historically embedded site, a positionality, a location, a standpoint, a terrain, an intersection, a network, a crossroads of multiply situated knowledges’”. Paradoxically, as Donna Haraway explains, “The only way to find a larger vision is to be somewhere in particular”.[3]

I confirm: the Nose to me IS this ‘particular’ point of presence, belonging and further navigation, of situated knowledge. And the inevitability of finding and owning your nose (or any other body part or your whole body if you wish) leads to the inevitability of finding and owning the Jewishness, in my case, and any other identity in a multiplicity of other cases.

The thing is, that I was never brought up as Jewish. I was raised by my great-grandmother Sonya, who loved me terribly and spoilt me with love and attention. What was never discussed, however, is that she had to change her full name after the Bolshevik’s Revolution in 1917, and live all her life under the fictitious identity of a person she created herself. The only reminder of her Jewishness was the package of matzah (unleavened flatbread that is part of Jewish cuisine), delivered to her every Hanukkah by a local Jewish community centre, which was allowed to function after the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991. Other than this package of matzah, Jewishness was off the table and I grew up in complete disaffiliation from this part of my ancestry. And I guess it would be fine if it wasn’t for my Nose! This treacherous nose, it would give me away! I cannot count the times I was thinking of getting a nose job done and ending my sufferings with this. Now I can only echo Kominsky by saying: “So I managed to make it thru high school with my nose!!”. And very happy that I did, as now I see this nose as maybe one of very few tangible points of departure of learning about myself, of belonging, of aching. I cherish it. I love it.

I’m wrapping up this letter here, as I want to save some other thoughts for the letters to come. I welcome everyone to follow the exercise that Nastija suggested earlier—draw your nose and follow the thoughts that this process brings.

Olya

-

A friend sent these messages at 2 in the morning.

-

Dear Olya and Katya,

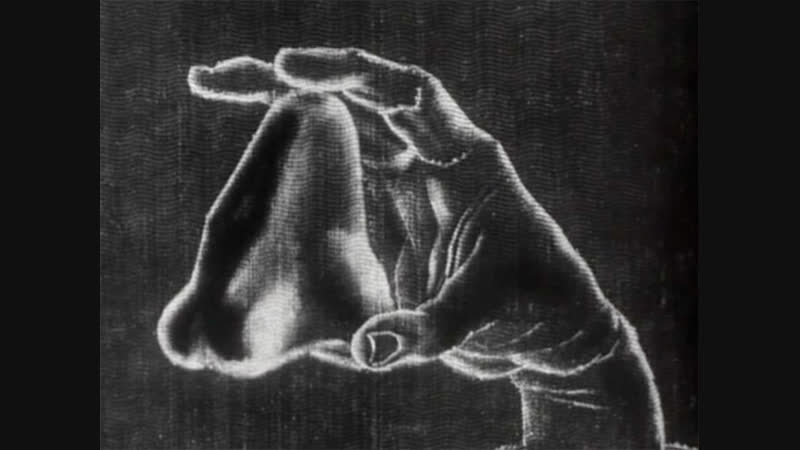

I had the strangest dream last night. It’s one of these cases when you wake up and only a fragment stays with you, while the rest is foggy and reachable, just like a word on the tongue that you don’t remember how to speak. I almost never dream in colour. In my dream there was a nose. I’m not sure who this nose belonged to. The nose was moving, kind of levitating through Amsterdam like an octopus. It had an innumerable amount of weird thread-like tentacles growing out of the nostrils. At the end of every arm there was a hand. It was swimming through the air.

Through a quick google search I just found out that dreaming about noses is apparently linked to intuitive knowledge that wants the dreamer to pay attention to something suppressed or ignored. But I think that I dream about noses because we are currently writing about noses, and especially because I reread Nikolai Gogol’s[4] The Nose[5] last night.

I reread this short story because I wanted to respond to your letter with a question: “What happens when the nose chooses to separate itself from its own body and begins to live a life of its own?”. Because, reading your words, Olya, always gives me the feeling that the nose wanders through the world with its own agency. Or, as you express it, it becomes this place of “situated knowledge” that then positions us in the endless puzzle of self-representation.

The story goes roughly like this: One morning Ivan, the barber, wakes up. For his breakfast he must choose between a cup of coffee or some bread. His wife is strict, and he cannot have both. He chooses the bread and as he cuts through the loaf, he discovers something solid. It’s a nose, and what’s worse, he recognises whose nose it is. It’s Collegiate Assessor Kovalyov’s nose, the one who prefers to be addressed as Major Kovalyov as he is mostly concerned with his status within society, and he’s addicted to the sensation of being respected. Ivan, horrified by finding the nose in his breakfast, decides to get rid of it. He throws it in the river. A moment later he is captured by a policeman. The same morning Major Kovalyov wakes up and wants to check if his pimple from the previous day has disappeared. We don’t know, but we know that the whole nose is gone. We don’t know why, but we know that the place where the nose used to be is now a flat, smooth surface. Oh, and he is not happy about it, because without a nose he can no longer take his place in the society of ‘respectable’ people. Suddenly, he sees a carriage. Inside there is a nose that he recognises as his own. He follows the nose through the city. Finally, there is a moment of confrontation. The confrontation between them happens to be in a church. Major Kovalyov explains his frustration provoked by the loss and tries to convince the nose to come back to his face: “For to go about without my nose, you’ll admit, is unbecoming…”. He lists all of the social contexts that he will now be excluded from, then concludes his argument by saying “After all, you are my own nose!” To which the nose replies “You are mistaken, my dear sir. I exist in my own right. Besides, there can be no close relation between us. Judging by the buttons on your uniform, you must be employed in the Senate or at least in the Ministry of Justice. As for me, I am in the scholarly line.” The nose turns its back to him and continues his prayer.

It’s striking how difficult it is for the body to forget its nose, while for the nose it is no big deal to forget the body. It doesn’t really need that relationship. As for Gogol’s satirical short story, of course it revolves around a man whose nose allows him to be part of ‘respectable’ society, and in the absence of it kind of closes that door. He got himself a face that is welcomed, which doesn’t apply to all faces. My grandmother has often told me a story, laughing as she tells it, about a game she used to play with her colleagues at work. She would ask everyone “Guess where I’m really from?” and people would name one country after the other. They would never guess right. She would always tell them that her place of origin was the one where she was at that current moment, and then her colleagues wouldn’t ask more questions so as not to not make fools out of themselves. Sometimes, she would tell them that she was the granddaughter of Alexander Pushkin, so they could figure out the reason behind the curly hair. The truth is, as I already told you, we don’t know where we are ‘really’ from. The truth is that this question makes me uncomfortable. My grandmother has always told me that I’m lucky that I turned out to be so white with straight, dark blonde hair. I hate when people ask me if she is “really!?” my relative and, to be honest,

I rarely know what to do and how to approach this kind of situation. I barely know what I want to say about it right now. I have no very specific point, apart from telling stories that, one by one, weave the complex web of our forgetting, our contradictions, and the truths of our fictions.

There is a subtle detail in Gogol’s nose story, that could easily be missed. It appears when the apparently utterly ridiculous character of Major Kavalyov is introduced. It is explained that he made his rank in Caucasus and the scholarly diploma can by no means be equated to those in St. Petersburg where the story takes place. Caucasus was further colonized by Russia between 1800-1864, and The Nose was originally published in 1836. When Major Kovalyov approaches all the major institutions (law enforcement, health, and the media) with the request to find his nose, no one is willing to help him. The nose returns to him suddenly and of its own will during his sleep. He celebrates the event by buying himself a ribbon of some order, even though he has never been decorated with any. I guess he came to the city to reinvent himself, to become a fiction as part of the collective history of many of us. The nose didn’t claim a country of origin, but it claimed to be of a scholarly line. It simply claimed an origin in knowing or study, that’s all we get to know of its belonging. Maybe this is something the body could not do in the system that it had to survive in, but that I don’t know, of course. As readers, we never find out why the nose appeared in a loaf of bread and the reasons behind its return.

With love,

Nastija

Illustration (1935) of Gregory Kroug, Russian iconographer and a priest who immigrated to Paris in 1931.

Stills from ‘Le nez’ (1963) Directed by Alexander Alexeieff, Claire Parker

Still from ‘The Nose’(1977) Soviet TV drama film, directed by Rolan Bykov.

-

My dear Nastya and Olya, my dear noses,

After I received your letters (thank you so much for inviting me into this conversation), I was thinking the whole time about this one thing I usually would tell: that I really did not know what was happening the whole time and that I, all these years, just smelled something. Intuitively, as a real nose, I started to use the notion of smelling as something which can help to find things that are not visible, things that have gone missing–lack language and form. Sitting in a house which was full of white porcelain, full of “furniture without memories”, maybe a big leather couch, two TVs, some indirect lighting but no carpet (for sure no carpet), some cacti and also this shelf with white plates and bowls stacked on top of each other, new enough to still be shiny. The only thing that was left for me was to train my smell. The point is that in my story there will never be such a thing as a dusty attic with some boxes full of photographs or documents, some never-sent love letters. And at some point, I started to understand that even if I imagine such a place in this house I am talking about, I would not find what I was looking for. Do you know this Soviet game called Sekretiki which translated means Little Secrets? Children dig a hole in the ground, throw in everything colorful they can find—blooming flowers, shiny stones, shimmering doll clothes—then they place a piece of glass over the pit, cover it with earth and run away. Only when they feel unobserved, they return, expose the spot again and view their secret treasures through the glass. When I heard about this game for the first time, I was pretty sure that these objects were carriers of memories that I was trying to find, and that they were still lying somewhere inside a pit in the courtyard of a house in Odesa. I grew up knowing that there are jackets that one has to, preferably, take off (in case this someone, at least, wants to achieve something): jackets which may then hang in a cupboard, maybe in this one house they managed to build in a new country, maybe even with one of these walk-in wardrobes full of clothes, or, in other cases, the jacket would even not hang there anymore, maybe it was sold at a market when they had to leave the apartment, or maybe it just disappeared. Somehow they got rid of it, and no-one remembers anymore how exactly this happened. Today this jacket is not accessible to vision, it has no touch, sound, or taste. Was it a warm jacket? They do not know anymore, really, she always says that she does not remember. Their energy when they packed their belongings into some plaid plastic bags and took their busses, leaving everything behind, was from this one moment on always directed to a future and never again to the past. For example, I asked her recently for the recipe of this cheesecake with raisins she used to make after I recognised the smell of warm quark somewhere around, and she said that she does not remember. She does not remember and they say: even better so! I have the feeling that people being asked about their first memory usually tend to connect it with a smell: this one specific soup a grandmother was cooking in a kitchen in a time before linguistic masks entered your life. But to come back to what I am trying to tell: today I am no longer looking for these objects. In my story, as in yours, there will be no material evidence. What, really, can a single object tell us when it is brought out of context and if there is no person who can tell you a story about it? And what if you suddenly realise that some of the stories you’ve been told were simply not true? She always had the tendency to repeat herself over and over again and at some point I stopped listening. Everytime she was talking to me, for example when we were sitting in a car—me in the back—her in the front, she would ask me if I was listening: “Are you listening? Do you hear me?” Usually she was telling me some recent scandals that were on the news. The thing that I became interested in was not necessarily what she was talking about, but how everybody said the same things over and over again with infinite variations. Over and over again until finally, if you listened with great intensity, you could hear their words rise and fall and tell all that there was inside them. Not so much by the actual words or thoughts they expressed, but the movement of their words and thoughts. While searching for these Little Secrets which might be found inside a pit I, without noticing, switched positions and suddenly it was me lying there. Surrounded by wind and wet soil, today the top of my nose is touching a piece of broken glass. And here comes the nose again. I hope I did not go too far from the nose, but I am sure that you see that I, too, am sharing this from my nose as a nose. Maybe there are not many other things left for such melancholic migrants as we are, than the trust in our noses. And I do not mean the smell of the soup which I, to be honest, don’t remember, but the intuitive knowledge the smells bring.

With a small shy hug to the ghosts that we always have smelled,

I send you my love,

Katya

-

My Dearest Носики,

As it sometimes happens, when people overhear an interesting conversation, they stop in the middle of a street and stick their noses into this conversation. I can feel that the amount of noses in this letter exchange is growing with each day. Snooping around, sniffing (because they are being sentimental, naturally) or wrinkling (because they are contemplating) or cold with a little drop on their tips (because the gas prices went up and we are trying to save some money). Hence, I say ‘my dearest noses’, as it’s not only me and my nose anymore. It is a choir of noses and Christmas is approaching, I imagine this choir singing joyful hymns. A joyful choir!

Christmas is a moment for sentimental contemplation (for me), and of thinking about the family. I received three letters this week about noses and, somehow, all of them speak of a nose as a painful part of growing up. These letters echo the beautiful words that Katya sent last week. Words about childhood and familial memories, partially blurred, partially invented, and partially real (or as close to being real as you can get with memories). These memories feed the silvery traces and threads of belonging that become more translucent with each year, shimmer, and eventually dissolve, unless we treat them with unwavering attention, day to day. I wonder if ‘growing up’ is the absolute opposite of ‘belonging’? And if our noses grow throughout the whole length of our lives—do they not want to belong? All babies are born with these miniature, characterless buttons of a nose, but as they grow, their noses become a whole separate thing, with their own character. The older we are, the more charismatic they become, departing from their generic, pre-adolesent form. But maybe it’s my thing…I just love old faces, with all their wrinkles, spots and weird noses with silver hair growing out of them.

Where were we? Yes, noses and growing up. I attach three letters below, preserving all the details and the teenage angst and frustration that comes with them. Let us celebrate the Nose as a symbol and an emblem of the rites of passage!

-

Letter #1. O.

Artificial Nose

I am 10 years old. I stand in front of my grandmother's three-winged dressing mirror and look at my nose in profile for the first time—I cry, I’m so shocked that I decide to save up for plastic surgery from school lunch money. I didn’t have enough willpower to do that, but since that moment I was constantly upset at the sight of my nose. For some reason I was OK with my eyes, lips and ears. Their shape correlated to the image of myself in my head, but the nose ... In my head I had a small nose without a protruding tip, so the ‘real’ nose felt like an alien that didn't suit my face and my character. The eyes are the mirror of the soul. But what about the nose? My nose was not the mirror of my soul. It was a mirror of my parents.

Until the age of 18, I was sure that I would get my nose done, but then I read The Beauty Myth by Naomi Wolf. The book impressed me in the most profound way, and I convinced myself that my dislike for the nose was imposed on me by society, that I must embrace its messy form, otherwise I would cave in to other people's standards of beauty. I shouldn't follow the lead of men who dictated the template for the perfect nose. I practiced this kind of persuasion in the back of my mind literally every time I saw myself in the mirror for many years. But the feeling that my nose should look different, and that there was some kind of mistake on my face, did not disappear.

At some point, I became interested in biology, especially genetics, and the prism of my view changed again. Now, for me, a person has become a set of nucleic acids that are passed down from generation to generation, while not even their ancestors had chosen their genes. Just as society dictates the ‘beautiful’ shape of the nose, so the DNA of our ancestors dictates what we end up with on our face. A certain combination of adenine, thymine, guanine and cytosine coldly me what the shape of my nasal bone, its lateral cartilages and muscles will be—a small composition on my face that does not occupy even a hundredth of my body, but causes a huge part of my anxiety.

If the nose is doing its job, then the DNA transfer from our ancestors was successful. But what is included in a nose’s job? Difficulty breathing is a sufficient reason for surgery, but why can’t psychological discomfort can’t be sufficient? My transgender girlfriend said “the only alien for you is your nose, but for me the alien is my whole body”.

What are the reasons for these feelings of discomfort?? Is it society’s beauty standards? Childhood trauma? Mental disorder? Or maybe it’s all in the DNA? It seems to me that when the causes are so vague that it’s almost impossible to find them, the most important thing is not the causes, but the very fact of the presence of discomfort. Without surgery, a person is unhappy, but surgery can lead to a happier life.

To fight for the recognition of the beauty of the noses inherited from our ancestors is the noblest of things. Everyone has the right to love and consider their large, hooked, wide noses beautiful. It is a right, but not an obligation. They also have the right not to love them, and to make themselves their own nose. When does protecting the rights of your ancestral identity become more important than your own happiness? When does the collective become more important than the private? Isn't there a slight tinge of fascism in this? Interestingly, after the operation, the nose loses its ancestors—its form no longer has genetic parents and one probably won't be told "you look just like your mother" anymore. But after an operation, you may look like yourself, the way you want to be. Someone may say that the new shape of the nose was dictated by the beauty standard, but isn't the congenital nose shape also dictated by the genes you never asked for?

I believe that the ultimate unit of measurement in this matter is the level of happiness. After the surgery, for the first time in my life I feel comfortable and cozy in my body. Passing by the mirror, I look into it with a feeling of gratitude, not despair. I couldn't even imagine it was possible not to experience this regular discomfort, which takes up so much energy that could be spent on more useful things than quiet fights with myself.

-

Letter #2. G.

The nose lesson

When I was a teenager, my nose helped me think independently. My nose was more important in the transition to an adult mentality than any other part of my body, or the body taken as a whole.

My nose was not the sole player in this: the process involved a group of neo-Nazi rugby players. Novgorod, a decaying Russian town with glorious history but bleak present, was the scene.

I was seventeen and friends with anarchists, anti-fascist skinheads, and punk musicians. It was extremely naive political activism mixed with subculture and socialisation. But they were deadly serious about it, and I took them seriously. On the streets of Saint Petersburg, my friends fought an uphill battle against neo-Nazis and their allies, football fans, whom they called ‘boneheads,’ to differentiate from the ‘skinheads’, the term they wanted to reclaim. Occasionally, I helped them defend hardcore punk music shows from the Nazi attackers.

And one evening in May, an alarming message appeared in our group chat: our intelligence uncovered an enemy plan. We were told that a group of rugby players allied with the boneheads was going on a punitive raid against two punks in Novgorod. It was said to be happening the next day. We had time to assemble only a small group—a dozen guys, perhaps—to try and defend them, and we left for Novgorod on the first train the next morning.

On arrival, we went straight to the building where the two punks lived. We knew the wait wouldn’t be too long, we noticed the opposition’s scouts tracking our movements. Soon, a group at least twice our size appeared. The fight was short. I was knocked down and kicked in the head, and so were my

comrades. Luckily, a babushka saw the fight and called the police; we were saved by their sirens.

The police kindly gave us a ride to their station. Those over eighteen were let go. But I and one other boy, both underaged, were left there overnight—by law, we had to be picked up by our parents.

When taking me home, my folks were considerate enough not to ask any questions. It was one of the classiest acts on their side. But when I inspected myself, having cleaned the face from blood in the shower, I noticed that my nose looked wrong. My parents protested: “It looks fine! You’re overreacting.”

It was tempting to rely on their sound judgment and just stay at home. The prospect of going to a hospital after spending a night at the police station was not pleasant. The medical gaze on top of state punishment, I thought. Seventeen is a great age to read Foucault...

I took another good look at my nose. It definitely looked wrong. I told my parents that I would be seeking a second opinion and went to the nearest A&E. A quick check found that my nose was broken. It required fixing to avoid breathing problems. I spent the next two weeks at the hospital, where they broke the nose again and put it into the right position.

Very little pain was involved, and the whole experience seemed easy and insignificant because I was seventeen. But I kept thinking: had I trusted my parents and stayed at home, I would be left with a crooked nose and potential medical issues. I realised for the first time what I knew theoretically, but never really experienced: my parents, and adults in general, were not omnipotent, they did not know better than me, they could give me the wrong advice. They were in a different

league but we were in the same weight category, in terms of reasoning.

In other words: my nose taught me an important and sad lesson about grown-up life.

-

Letter #3. L. (transcribed from a series of audio messages from Instagram)

So… I used to have a little nose and cute round cheeks and, yes, I watched too many anime cartoons. But then I turned 24, and I haven’t even noticed how but my face has changed drastically . It has become long, my cheeks have disappeared, and the nose, my nose, has become big. I started to develop dismorphophobia as my nose seemed much bigger than it actually was. It just kept growing inside my head! And the problem was that I could no longer fit in with anime cartoons with such a nose, as I saw it back then. I didn’t want to grow up. I even started to think of getting surgery. But one good man talked me out of doing this. He told me that the nose is the place where I am encountering the ‘real’, and if I chop off my nose I will, in a way, ‘castrate’ myself and won’t be able to interact with the ‘real’ to a full extent anymore. I am still grateful to this man, as the dismorphophobia faded, as well as this belated puberty. And, you know, I wouldn’t have had the surgery anyway, I had no money to do this. But, out of curiosity, I went to see a doctor and he told me that I have a man's nose! And he said that he would make my nose flatter and more Asian. And as I always had questions around my gender, this nose remark of course triggered more confusion. I still think that doctors should not say stuff like this to their patients. But now I look at myself in the mirror and I still don’t think I have a man’s nose!

-

A couple of days ago the last message arrived to provide a solid closure to the situation around noses and childhood trauma.

And instantly I remembered something that I would rather not: how my nose was broken by a sadist otolaryngologist when I was a kid. And it was never fixed. It gave me life long hypochondria and epic snoring abilities. I am the champion when it comes to snoring. Which makes my nose also a very problematic part of my private life. Let’s leave it here…

Through this letter exchange I arrived at so many points of encounter with the nose, each time growing closer to other people who shared with me their first-nose narrations. Very private, very touchy, very sensitive. Through these noses I found the feeling of belonging I was craving, but not toward my family or to a distant geography of my childhood, but to a rather unplanned assembly of people thinking with and about noses. This weird nose-belonging is something that makes me warm and at ease. I look in the mirror. I like what I see.

Olya

-

Dear melancholic migrants (Katya, I’m adopting this term!),

I’m writing my last response in our correspondence. It’s a knot on a thread beaded with fragments of our noses, still moving at the sentimental speed of a body composed of as many possible selves as there is possible time. I know that we will continue this conversation. Sometimes I talk to you inside my head. This is what the rhythm of letter writing does to you—you save your thoughts for later so you can write as an echo in immediate response to the words directed to you.

Katya, I imagine this place as digging a hole in the ground of the Sekretiki, leaving my collection of feelings to look at later, and till then they will live a life of their own. I’ll let you know how they speak or how they sing someday in the future.

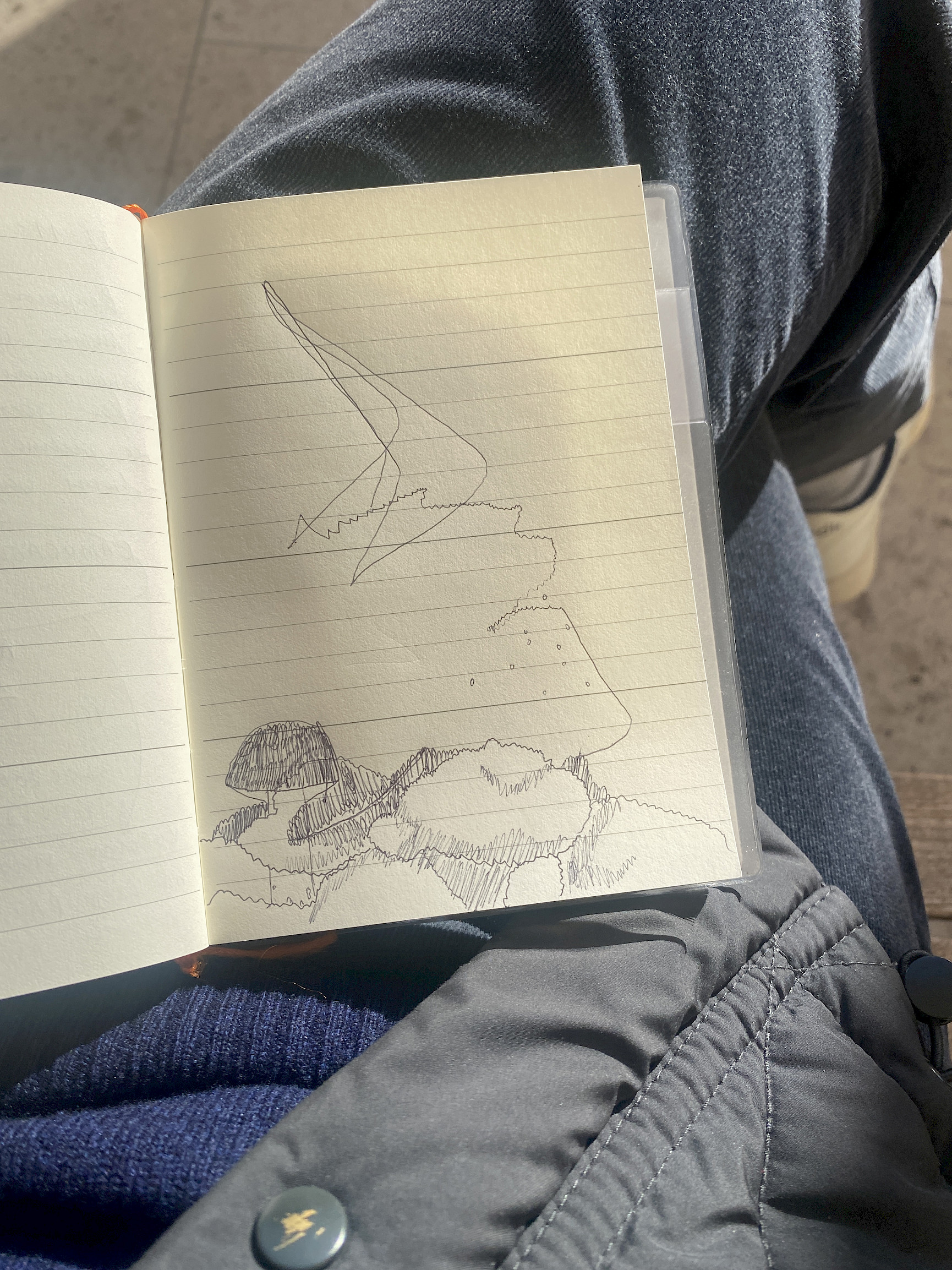

And Olya, I have been returning to the landscape. In a way it has been there since it entered this conversation. I’ve been sitting on the train from Amsterdam to Rotterdam to the Hague and to Amsterdam and then the Hague, and then Rotterdam and then repeating and repeating. I’m sending you a collection of noses observed from the view of the window. I want to let you know that I’ve seen in the sunrise and in the sunset. It's the end of December now.

And yes, I think you’re right, there is something warm about this nose-belonging. We weave through our speech a sensation of the familiar, seen as a mirror in a story that is not our own, but that we nevertheless carry in our own variations. There is a form of care in receiving and sending a letter. It’s movement that holds one in a simple gesture of concentrated attention. I value that. We will never be alone.

Dears, thank you. I’m sending you love and drawings of landscape noses.

Nastija

-

Любимые,

I had to think of you: Yesterday I was in the theatre in Vienna and they played Cyrano de Bergerac. A play about a brilliant poet and swordsman in Paris in 1640 who finds himself deeply in love with his beautiful, intellectual cousin Roxane. Despite Cyrano’s brilliance and charisma, a shockingly large nose (this is what the short description says) afflicts his appearance, and he considers himself too ugly even to risk telling Roxane his feelings. This, together with your letters, made me remember how I was sitting on a German train, the ones where you have a small table in front of the seats, and I was leaning my elbow on the table and my nose against my hand. It was an attempt to sculpt my nose as I wanted it to be, into a shape like everyone else, with this small skin-part coming up and not down. But this is many years ago now. Like you, I did grow up. Yesterday on the train something different happened, out of nowhere. A Turkish worker told me: “The word absence suggests a non-presence, a loss, being nowhere like a non-appearance or a lacking.” I answered with an understanding smile, another melancholic migrant I thought, while a mother and a daughter, sitting next to us, were playing the game Memory. These are the things that happen when you follow your nose I guess. While everyone is walking forwards, one foot in front of the other, I am walking forwards and at the same time backwards, one foot in front of the other, one foot behind the other, or sometimes maybe even two? I used to be one of these people who were thinking in between the many possible versions of gray, never at the edges of a blank and empty white, or a dwelling, almost comfortable black. In place of following a map, I learned to follow my nose and I found way markers, each pointing in a different direction. And at some point I found you, and we found all these other smellers, first-and-second-nose-narrators, melancholic migrants, wanderers with their really beautiful noses, and I hope that there are many things left to smell on our shared journeys.

With a less shy hug to the ghosts that we always have smelled, I send you my love,

Katya

COLOPHON

Letters written by Olya Korsun, Anastasija Kiake, Katherina Gorodynska.

With contributions from Olga Marchenko, Evija Kristopane, Bernice Nauta + dear friends who wished to stay anonymous.

Proofread by Rosie Haward

Commissioned by Extra Intra: the Editorial Board of Intercurricular Programmes from the Gerrit Rietveld Academie/Sandberg Instituut.

Amsterdam, 2023

FOOTNOTES

Jesse Darling, “A Letter to the translator”, 2018, https://accessions.org/article4/a-letter-to-the-translator/

Oksman, Tahneer. 2016. "How Come Boys Get to Keep Their Noses?" Women and Jewish American Identity in Contemporary Graphic Memoirs. Columbia University Press

Oksman, Tahneer. 2016. "How Come Boys Get to Keep Their Noses?" Women and Jewish American Identity in Contemporary Graphic Memoirs. Columbia University Press

Ukrainian writer (1809-1852) who is often claimed to by the Russians to be Russian

The Nose, Nikolai Gogol, https://www.gla.ac.uk/0t4/crcees/files/summerschool/readings/Gogol_TheNose.pdf