#6: Tender Attunements

Part A

Meant to be heard in any space of the Institution occupied by other bodies and preferably with headphones

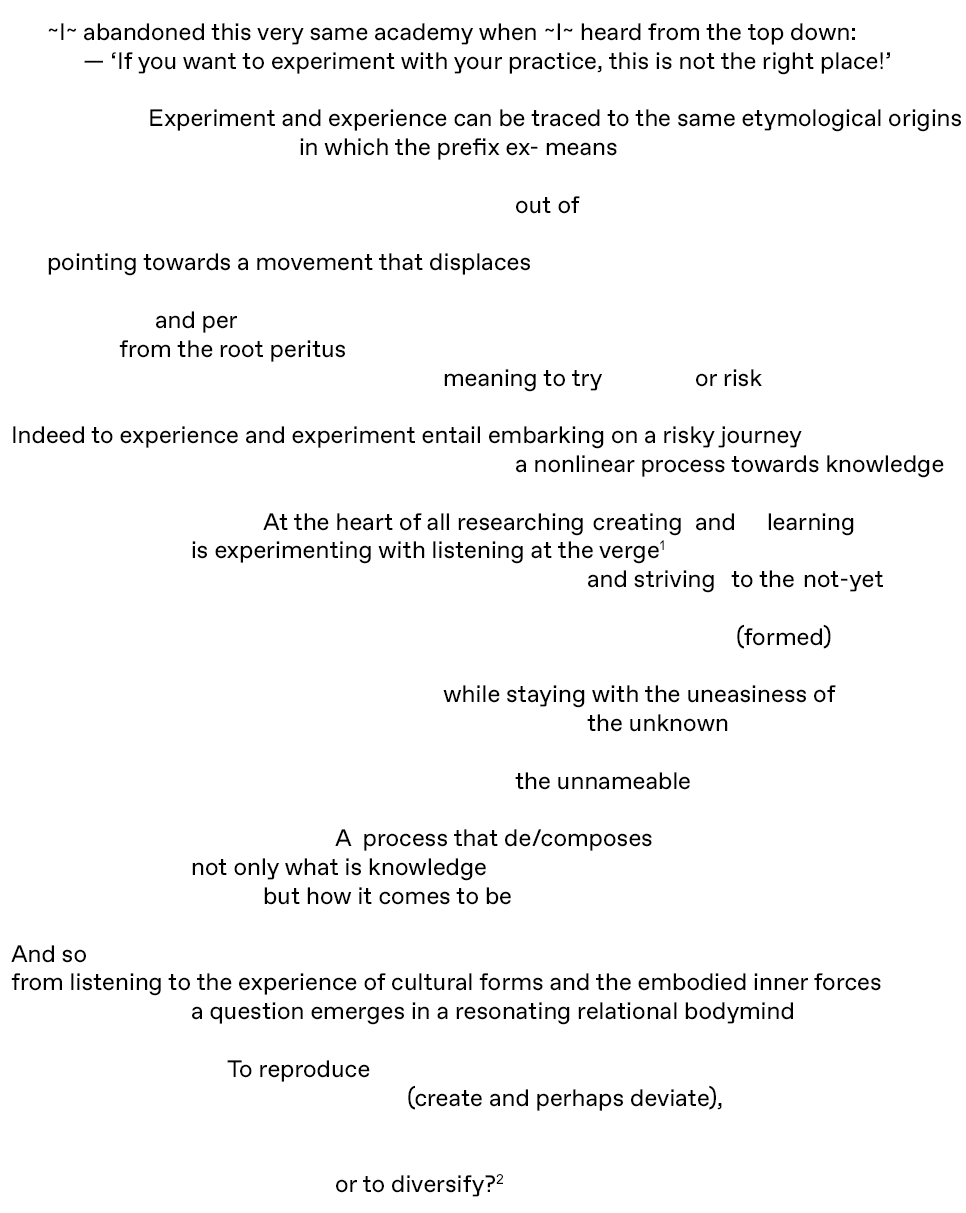

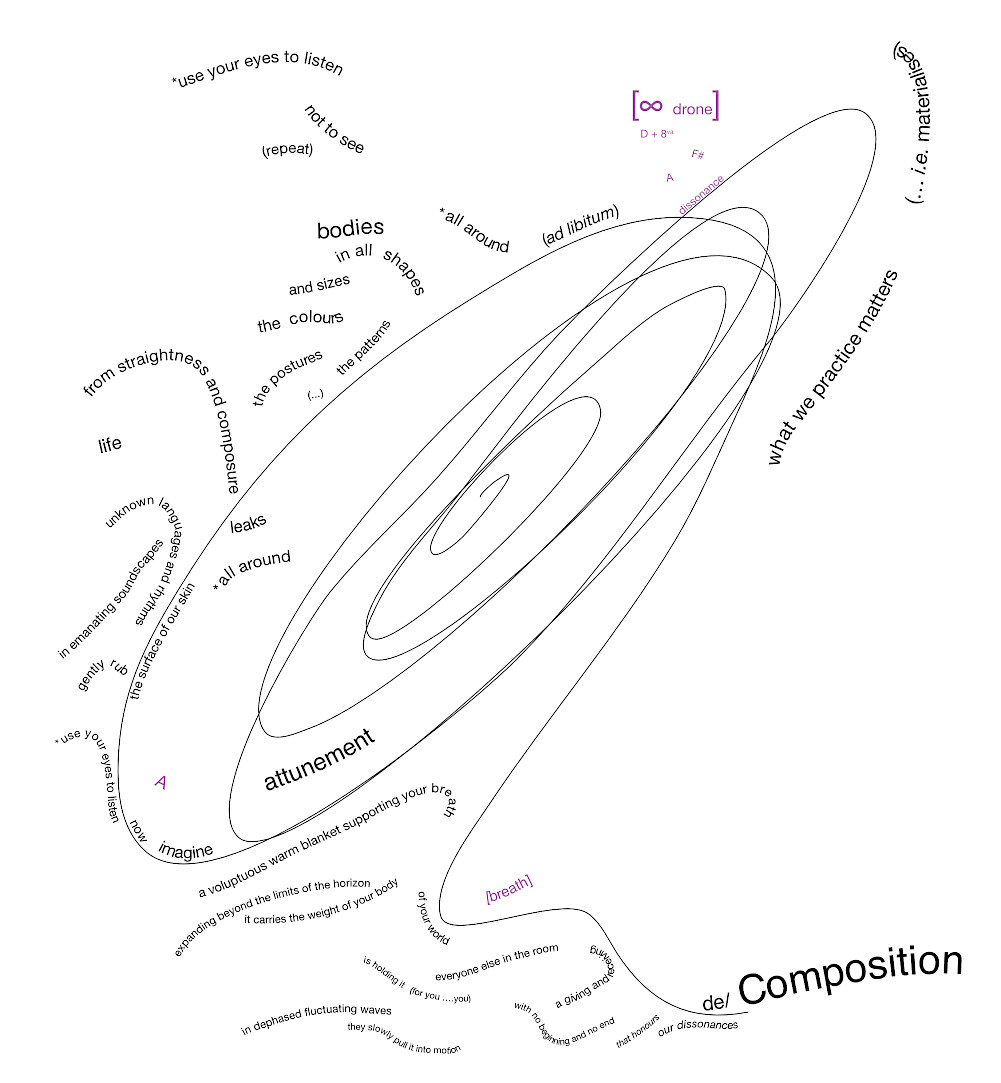

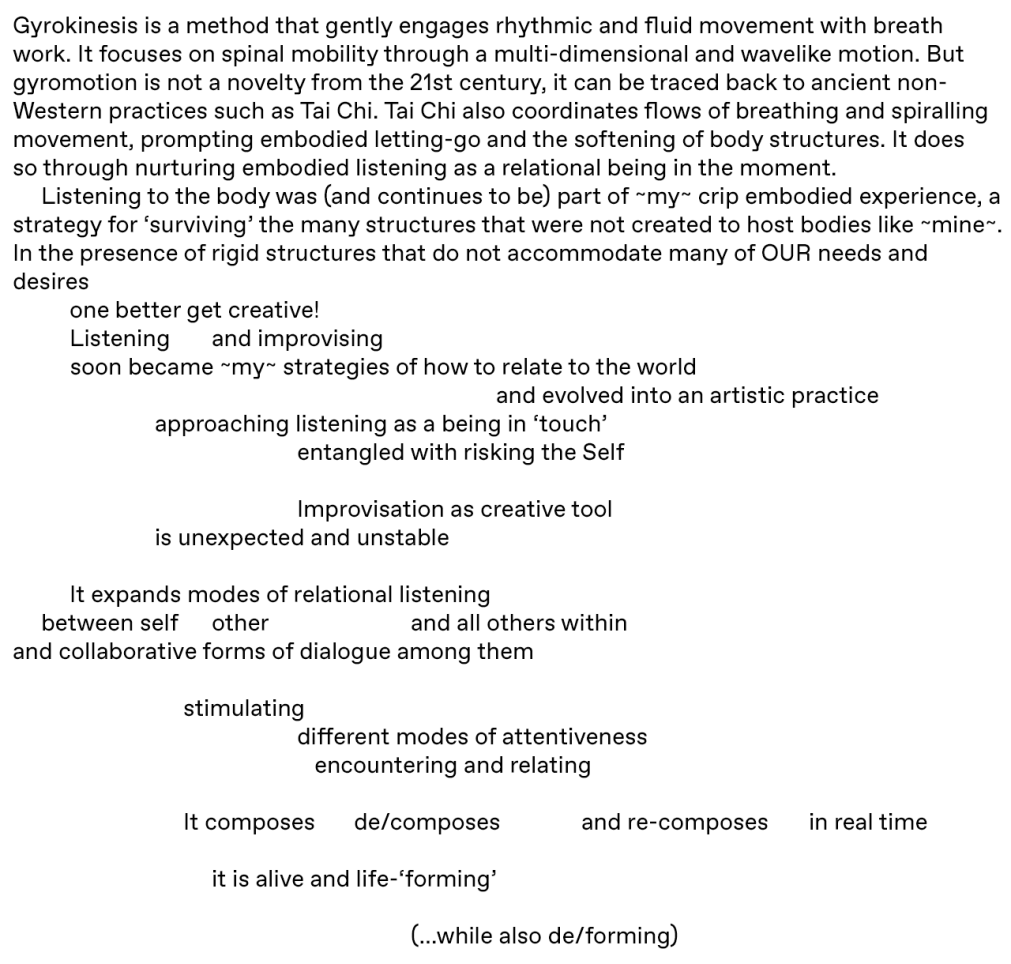

This contribution is based on a research project that started in 2019 between ~I~ and {I}: ~Angelo Custódio~ and {Jules Sturm}; two ‘I’s that, in and outside of this text, often become a we. When beginning our collaboration at the Sandberg Institute, we were both keen on developing new practices that would destabilise us in our divergent (academic and artistic) disciplined ways of working, with the goal to produce alternative ways of knowing, learning, and teaching. The initial motivation to turn to each other in order to challenge our habituated practices—in classical singing and academic writing—was sparked by a shared commitment to queer and crip experiences, which we were each exploring in significantly different ways. However, we both identified with the writings of theorists from disability studies, queer theory, feminist activism, and critical pedagogy. Our different professional and educational backgrounds, and the seemingly incompatible or at least contradictory worlds within which we usually developed and presented our works, generated a shared desire to set these worlds in dialogue with each other. As our collaboration was foremost informed by an embodied practice, besides the intellectual exchange, and dialogic forms of reading and writing—and as we lived in two different countries—our works-in-progress got stuck when COVID-19 hit. So as not to lose touch with each other and our project, we engaged in joint physical exercises (gyrokinesis) over zoom, while realising that we would not be able to continue creating new practices over physical distance. In addition to the fact that we were not only inexperienced, timid, unadventurous, and (psychologically) overwhelmed by the sudden and brutal increase in communication through digital media, we felt the loss of shared sensuous experiences. These sensory encounters are so nurturing (if not vital) to the exploration of our relational practice, which we wanted to be simultaneously alive and decomposing.

Conceptually and experientially, we start from de/composition, a concept developed by disability studies scholar Robert McRuer, which we attempt to turn into a practice. Composing and writing theory comes with structuring, ordering, cutting, limiting, and sculpting ideas, words, and text—almost endlessly—with the goal always to produce a finished product: an article, a presentation, a blog entry. Through crip theory, we realised that embodied knowledge production will have to engage in the difficult but necessary task of continually resisting the tendency to focus on finished products. And it must resist ordering and polishing ideas into perfect wordings, sentences, and paragraphs. Instead, the desire of crip theory is to unsettle stable forms of writing.

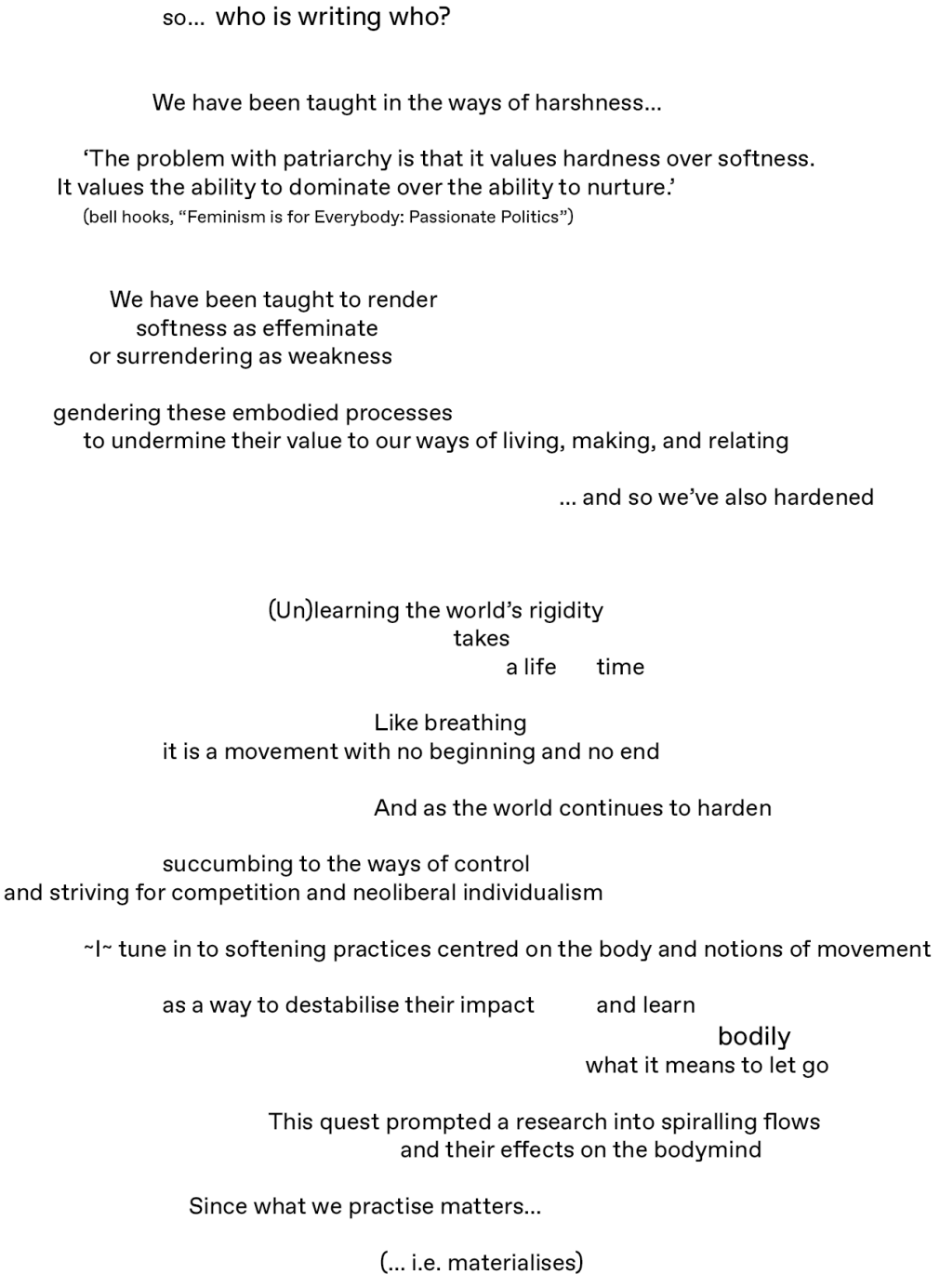

To be out of touch—bodily speaking—literally disconnected us from our delicate sprouting of thoughts and actions. To let go of the urge to keep producing became a call for more tenderness towards ourselves and our work, as well as a reminder that what we hoped for in our collaboration was to become attuned to each others’ and the worlds’ needs for vulnerability, softness, relational ways of listening, and importantly: more critically intimate forms of learning and teaching.

Part B

Meant to be heard in any space of the Institution occupied by other bodies and preferably with headphones

Writing as knowledge-producing practice, which we have both habituated and perfectionated in different ways, is structured by specific protocols and cognitive processes that are demanded by the technology of literacy. Literacy, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, describes the ‘unreflected capacity of being able to read and write.’ But alphabetic writing can also be interpreted as a technological system that operates through a corporeal principle. It engages directly with the body of its user, makes bodily demands, and has physical and psychological effects. The writing process produces the so-called alphabetic body, which in turn points to the intimate intertwining of bodily practices of perception and cognition.

Literacy as an embodied practice calls for the acknowledgment of its material consequences for the knowledge it can or cannot produce. All forms of literacy have material effects and are based on material conditions, as ‘the sedimented effects of bodily practices co-shape the human mind and the ways in which we perceive and make sense.’ (Maaike Bleeker, 29). Yet, these effects and conditions are rarely acknowledged as ‘[traditional literate] acts aim[ing] at dissociating mind from body. To practice literacy is, at the very least, to disguise and repudiate the body.’ (Carolyn Marvin, 132) In consequence, as a writer on embodied knowledge production, {I} had to become suspicious about the tools {I} was using for {my} thinking. As much as ‘literate thinking’ is a resourceful skill, its means of production pose a few crucial problems, which {I} felt {I} must confront by at least acknowledging their colonial, gendered, racist, yet disembodying history.

We want to understand literacy as a way of mattered/materialising perception, rather than just a form of cognition; literacy as a practice incorporating voice, tone, feeling, gesture, movement, smell, taste, desire, or touch. Such literate practice is prone to constant transformation, as it moves and flourishes by engaging in exposure to other bodies, minds, and sensations, and it will necessarily be practised differently by different bodies.

Corporeal literacy might be a tool to provide us with a new alphabet for embodied knowledge production. It blends two concepts into one, and transforms both elements: corporeality and written language. The two concepts seep into each other, decompose and recompose, destabilise yet support each other. Corporeal literacy is a theoretical concept as well as the name for a means of doing literacy otherwise. It names a research practice that incorporates and questions {my} literate skills in exchange with, and sometimes in conflict with, other skills of communication. For {my} theory-making practice, it became crucial to train corporeal literacy as an active form of perceptual cognition that takes into account its own means of embodied production; one that makes space for the material conditions of those theoretical concepts that {I} have been writing about for so long: vulnerability, care, monstrosity, queerness, disability, failure, conflict, desire, and disorder.

However, as much as we find corporeal literacy a useful term, we do not want to understand it as an ordering principle to ever be flawlessly performed. Rather it is a gesture, a communicative capacity, or a temporary vocabulary that gives us tools for experimentation, through which bodies can express themselves and be read or listened to more fluidly, and through which we can teach and learn other, more processual forms of knowing.

Our collaborative process did not start from concerns around teaching and learning. Yet, in retrospect, we can trace our common ground back to an educational setting. In 2018, ~I~ was graduating from The Master of Voice, while {I} was teaching a course on embodied theories at Critical Studies, both at Sandberg Institute. The institutional occasion for us to meet served to trigger what we later learned to identify as the educational value in excess of the curriculum (Erin Manning, ‘Radical Pedagogies’). So, while we were not focused on pedagogical matters, we came to realise that the art school provided us with an opportunity for interweaving questions of alternative knowledge production with processes of artistic learning, or, as Manning describes it: ‘Make learning a weave’ (E. Manning, ‘Radical Pedagogies’).

As both our teaching practices took different paths from then on ({I} taught theory within and at the edges of academic and higher art-educational settings; ~I~ taught performative artistic practice in institutional and non-institutional educational settings), we might have both neglected the impact that our collaborative process actually made on our individual teaching practices. Only when we started to discuss our approaches to teaching, and eventually taught as a team, did we notice how the mutual challenge of one another’s research practices and tools had an effect on how we address and relate to students in diverse disciplines (fine arts, design, dance, art education, art theory, transdisciplinary artistic practices). And when talking to students, they shared that they had noticed these impacts, describing how our classroom became a space for experimentation and collective efforts in what it means to learn. Against linear, disciplined, planned, ordered, and prescribed forms of teaching and learning, our shared time and space became joyful and tender.

While the sources of some of these impacts remain opaque to us, we can articulate some of them as relating to the main concerns and practices in our process of embodied knowledge production. They partly relate to Erin Manning’s ‘10 Propositions for a Radical Pedagogy’ (2015), partly to our own collaborative strategies. First, we recognised the fragility of learning (E. Manning) as it takes place in social spaces in which embodied (and affective) needs or desires are often repressed or remain unrecognised, yet reflect the very instabilities and intimacies that an embodied approach to education brings. Second, the aspiration for de-stabilising each other’s and our shared processes of composition (in writing and voicing) were experienced by the students as a relief, concerning their own expectations of how ordered or indeed composed their learning was supposed to be. Destabilisation in the classroom, however—more pronounced than in our twosome working chamber—brought about a special need in educational settings: the need to create an atmosphere of comfort, fun, critical intimacy, softness, slowness, and a culture of relational listening.

If we want to work towards further acknowledging, addressing, and attending to these special educational needs in higher art education, we—as responsive teachers and learners—must surely revise some hitherto neglected or even obstructed, and potentially itchy, elements of ‘school culture.’ We need to: confront chrononormativity[3] and embrace crip time(s); this involves resisting efficacy and being wary of exalting ideas of productivity and performance.[4] Unsettle competitive environments and discourse by nurturing relationships and building unfamiliar, unknown, or silent alliances across institutional roles and hierarchies. Not ‘make sense,’ but generate acts of silliness,[5] create spaces of wildness,[6] and engage in experiences of the non-sensical, yet more-sensuous.

References:

Bleeker, Maaike. "Corporeal Literacy." In: Daniel Neugebauer (Ed.) Re_Visioning Bodies, 2021.

Brooks, Peter. Reading for the plot: Design and intention in narrative. Harvard University Press, 1992.

brown, adrienne maree. emergent strategy: shaping change, changing worlds. AK Press, 2017.

Condorelli, Céline (Ed.). Support structures. Sternberg Press, 2009.

Einstürzende Neubauten, „Die Befindlichkeit des Landes“. Silence is Sexy. Song, 2000.

Fischer, Berit. “On the Notion and Politics of Listening”. https://www.making-futures.com/listening/ (8 May 2023).

Freeman, Elizabeth. Time Binds: Queer Temporalities, Queer Histories, New York, USA: Duke University Press, 2010.

Halberstam, Jack. "Wildness, Loss, Death." Social Text 32.4 (2014): 137-148.

Halberstam, Jack. The queer art of failure. Duke University Press, 2020.

hooks, bell. Feminism is for everybody: Passionate politics. Pluto Press, 2000.

Hurtado, Aida. "Theory in the flesh: Toward an endarkened epistemology." Int. Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 2003.

LETHE, Izidora I. Softness. double screen video, ceramics, 01:45, 2018

Loveless, Natalie, and Carrie Smith. "Attunement in the Cracks: Feminist Collaboration and the University as Broken Machine." Feminist Formations 34.1 (2022): 272-294.

Marvin, Carolyn. “The body of the text: Literacy's corporeal constant.” The Quarterly Journal of Speech, 1994.

McRuer, Robert. Crip theory: Cultural signs of queerness and disability. NYU press, 2006.

Pintilie, Adina. Touch Me Not. Film, 2018.

Samuels, Ellen. “Six Ways of Looking at Crip Time.” Disability Studies Quarterly, 2017.

Voegelin, Salomé. Listening to Noise and Silence: Towards a Philosophy of Sound Art. Continuum Books, 2010.

Notes:

‘The verge is a new form of knowledge that’s been there all along. The only reason it hasn’t stood out is that it activates a kind of value that resists evaluation. We just couldn’t see it, we were so busy with evaluations. This might be to its advantage: it still has the potential for creating new forms of value, new useless ways of valuing experience in the making.’ (Erin Manning, 10 Propositions for a Radical Pedagogy, or How To Rethink Value: 208)

In the keynote lecture The Micropolitics of Thinking: Suggestions to those who seek to deprogram the colonial unconscious, Suely Rolnik mentions the work of Lygia Clark Caminhando (WALKING) from 1963. In the work, the artist performs cutting the surface of a paper Möbius strip. When arriving at the same very point of the initial cut, a choice arises: to reproduce the initial cut or to diversify? As a result of choosing differently, the initial shape of the Möbius strip increases significantly. In opposition, continually iterating the same initial cut produces, as Suely mentions, ‘(…) a generic life, a sterile life, a miserable life [laughs].’

By ‘time binds,’ I mean something beyond the obvious point that people find themselves with less time than they need. Instead, I mean that naked flesh is bound into socially meaningful embodiment through temporal regulation: binding is what turns mere existence into a form of mastery in a process I’ll refer to as chrononormativity, or the use of time to organise individual human bodies toward maximum productivity. (Freeman, 3)

Natalie Loveless and Carrie Smith ‘invite us to attune generatively to brokenness [of university infrastructures] as a site of differential solidarity—where right action is situationally developed in communities of care that work to take the time needed to dialogue and resist the non-performative virtue signalling (and speed!) of call-out culture at its monologic worst.’ (Loveless & Smith, 290). From a queer-crip perspective, the concept of infrastructural ‘brokenness’ is important as it shifts the burden of ‘function’ from individual (so-called broken) bodies to collective and collaborative efforts of working within or with the brokenness of the institution.

Jack Halberstam’s theory of the queer art of failure demands to take seriously acts of silliness, stupidity, or forgetfulness as forms of unknowing/unlearning that resist and mimic predominant discourses of success, (re)production, and power.

Halberstam references Michael Taussig and José Esteban Muñoz on their respective decolonial and queer flirtings with the concept of wildness as a ‘space of unmeaning and un/being where darkness and light, self and other, order and chaos slip out of their orderly opposition and the symbolic order of signification itself falters and collapses.’ (Halberstam, 2014: 139). Halberstam proposes ‘to unleash the wild within knowledge production itself’(139) that ‘[seeks] out a queer vitality […] that skews toward collapse and works always on behalf of failure.’ (147)